The Potawatomi People

The Potawatomi were the last of a number of Native American tribes to inhabit the local area. They were introduced to the Europeans as the Potawatomi, which roughly translates to “people of the place of fire.” They referred to themselves, however, as Neshnabek, meaning “true people.”

Little is known about what territory they occupied before the arrival of Europeans. There is evidence that in 1634 the Potawatomi lived in western Michigan on the shore of Lake Michigan, before conflict with other tribes forced them to migrate to northeastern Wisconsin. There they established alliances with the French and became involved in the fur trade. The subsequent southward expansion of the Potawatomi was prompted by the weakening of the Algonquian tribes of Illinois, which had struggled through years of disease and warfare against the Iroquois. By the mid-18th century the Potawatomi were firmly established in northern Illinois.

The Potawatomi who inhabited what would become Lake Forest continued to live in much the same way as their forbears. They engaged in hunting and fishing, as well as a limited amount of farming. Signs of the times, however, were their use of horses, heavy involvement in the fur trade, and increasing dependence on European traded goods. Contrary to modern assumptions, there is little evidence to suggest that the Potawatomi had tribal chiefs prior to European arrival. Instead, local clan leaders with limited roles were the recognized authorities. By the time the Potawatomi had arrived in Illinois, however, years of dealing with the French had led to the development of more powerful, centralized chiefs who could speak on behalf of the tribe. As regards religious practices, the Potawatomi made no distinction between the religious and the secular—religious beliefs and practices were part of daily life. Each clan of the tribe was a religious as well as political unit, with seasonal rituals and celebrations.

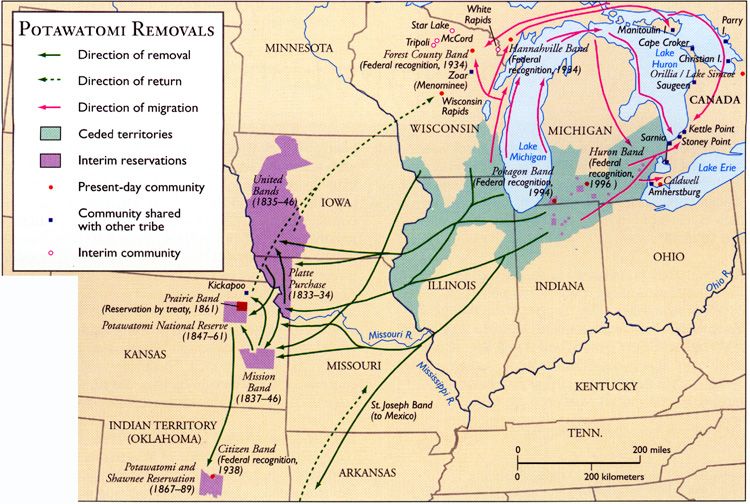

The French and Indian War (1756-1763) and the corresponding decline of French power in North America created division within the Potawatomi (who by this point were spread from Detroit across southern Michigan, up through Door County in Wisconsin, and down across north-central Illinois). Some Potawatomi remained loyal to the French and staunchly anti-British, while others embraced a new British alliance and went on to fight against the American colonists in the Revolutionary War. Conflict between the newly sovereign Americans and the Potawatomi (as well as many other tribes) continued with vigor until the Treaty of Greenville was signed in 1795.

In the years following the treaty the Potawatomi lost vast tracts of land as part of subsequent treaties with the American government. As their territory shrank, it became more difficult to successfully hunt game. They were thus increasingly dependent on government annuities, in addition to fighting widespread alcoholism. Two major events—the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the Black Hawk War of 1832—enflamed white sentiment against the Potawatomi and other tribes, and increased support for the “resettlement” of the tribes west of the Mississippi River.

The last major treaty was signed in 1833, at a large gathering of Native American tribes in Chicago. There the Potawatomi ceded the last of their territory east of the Mississippi, including what would become Lake Forest, in exchange for land in Iowa in Missouri and cash annuities. The Potawatomi removal began that year, and nearly all were gone by 1840. This relocation included the Trail of Death of 1838, a 660-mile march from Indiana to Kansas during which more than 150 Potawatomi died, most of them children. Those removed by force traveled to Missouri, Iowa, and Kansas, while others fled to Michigan, Wisconsin, or Canada. Today, there are Potawatomi tribes living on reservations in Michigan, Wisconsin, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Canada.

It is perhaps not so very surprising that it is difficult to see the traces of Potawatomi habitation of Lake Forest. After all, they only occupied the area for about a century before their forcible relocation, and since that time industrialization and huge population booms have largely obliterated what few signs they left. One way their influence can be seen locally is names. Aptakisic Junior High School in Buffalo Grove, for example, is named for a Potawatomi chief of the 19th century. The chief, whose name means “half day,” is also the source of a common misconception—it is his name, not the length of the journey into Chicago, which gave the name to Half Day Road. Some other names that originated with the Potawatomi include Waukegan (meaning “fort” or “trading place”) and Mettawa, another Potawatomi chief. Other remnants of the Potawatomi are streets such as Green Bay Road, Belvidere Road, Fairfield Road, and Milwaukee Avenue: these winding roads are built on what were originally Potawatomi paths. Such subtle signs are some of the only visible clues that the Potawatomi were here at all.