Cascarano Family

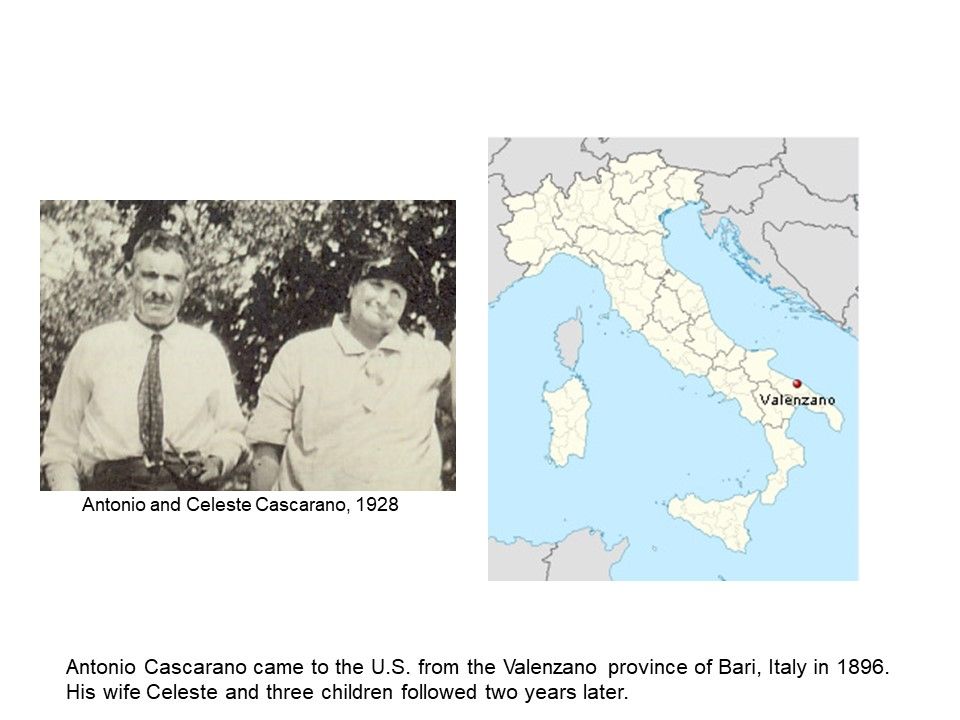

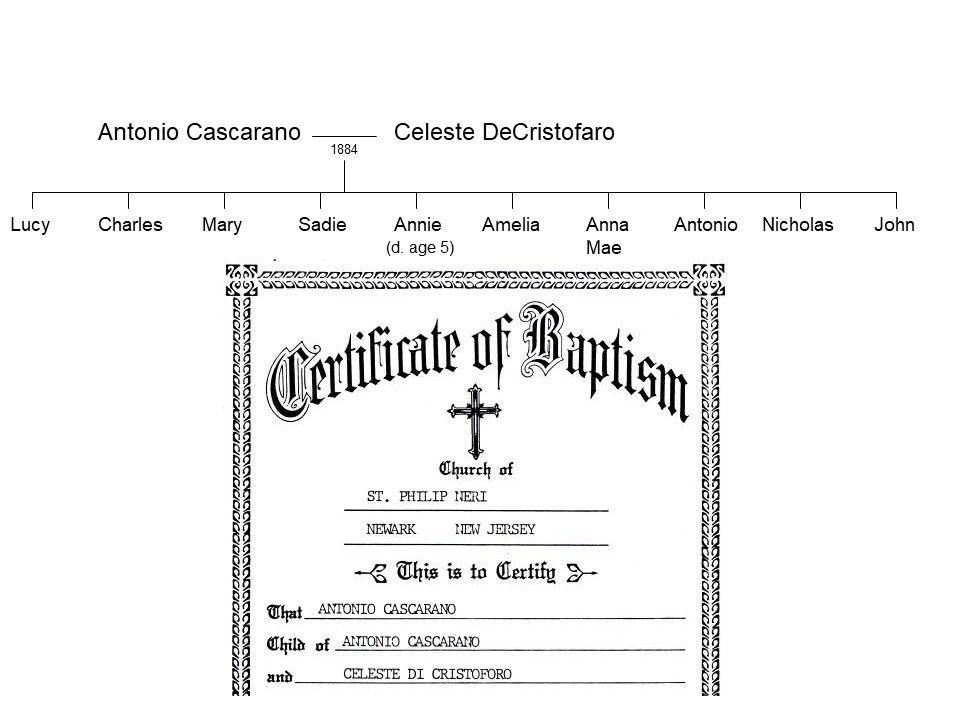

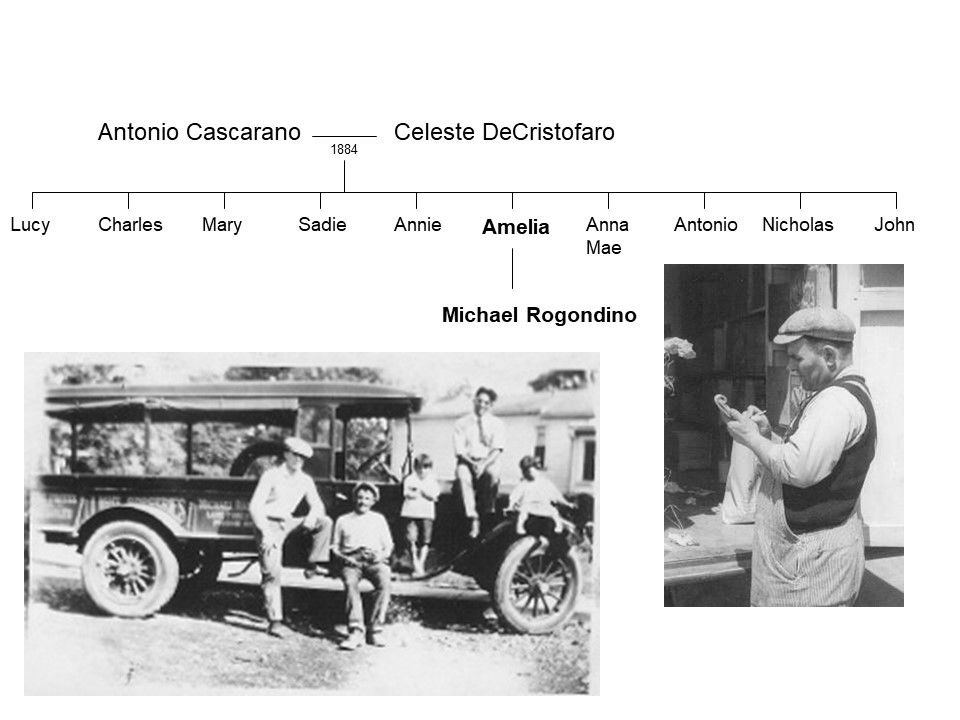

For generations, the Cascaranos had lived in the Valenzano province of Bari, Italy, located in the southeast along the coast, about 250 miles from Rome. In 1896, a young tree trimmer named Antonio Cascarano made the journey across the Atlantic to the United States; two years later, he sent for his wife Celeste and three small children, Lucy, Charles and Mary – the youngest of whom Antonio had never seen.

The Cascaranos settled amongst friends and relatives in Newark, New Jersey, where seven more children were born to Antonio and Celeste: Sadie, Annie, Amelia, Anna Mae, Antonio, Nicholas and John. Antonio worked on a dairy farm and, according to family stories, for one of Thomas Edison’s New Jersey factories.

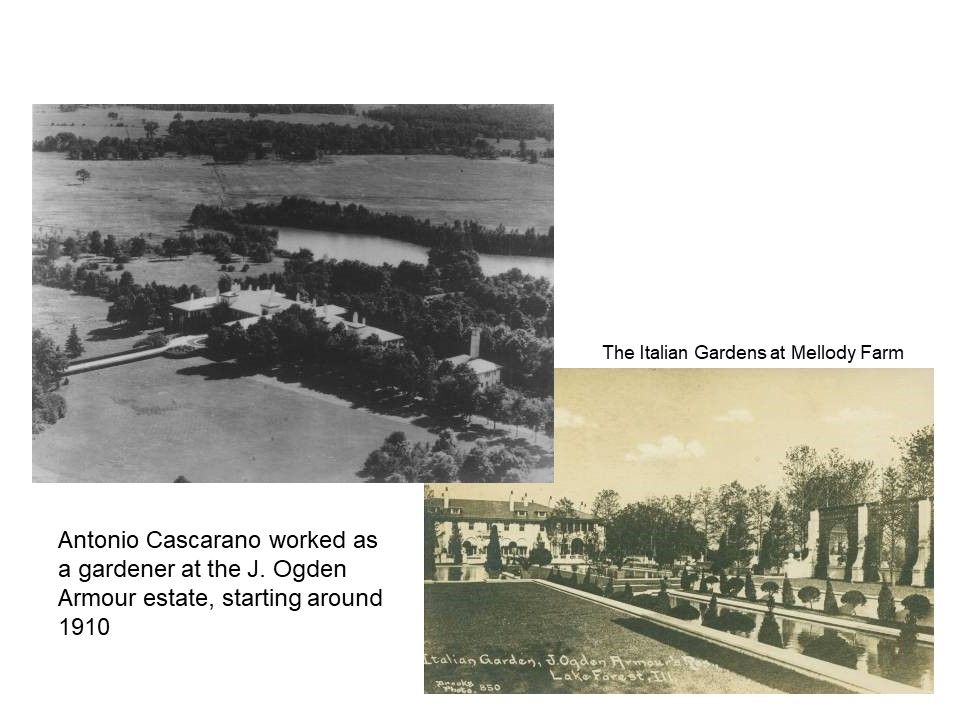

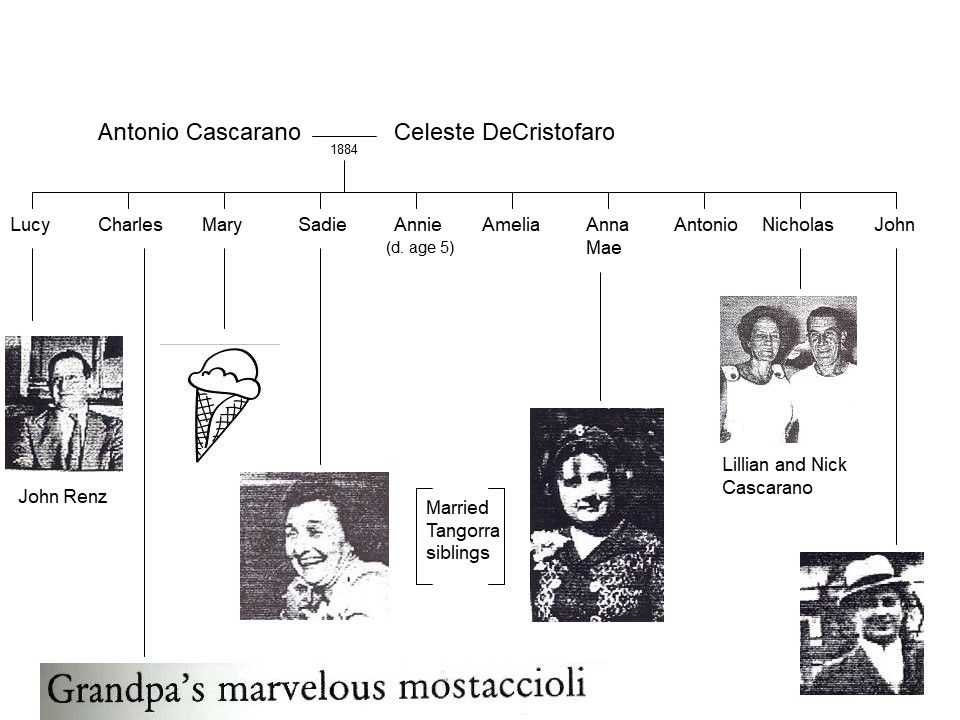

In 1906, Charles Cascarano visited an aunt in Chicago, and was impressed enough with the place that he convinced the whole family to move there by 1910. Antonio and Celeste and most of their children rented a home in Chicago, where they were listed in the 1910 census, but their oldest daughter Lucy and her husband John Renz settled up north in Lake Forest. John was a cabinetmaker who had constructed casings for Thomas Edison’s phonographs back in New Jersey, and the cabinetmaking trade was in demand in growing Lake Forest. Soon, Lucy’s father Antonio found his gardening skills were sought, too, by the many new Lake Foresters who wished to model their landscapes after the designs of Italy. He began working as a gardener at the recently completed J. Ogden Armour estate Mellody Farm, where the gardens had been designed by Jens Jensen. The Cascarano family moved up to Lake Forest by 1911, residing in the home on Woodlawn which would remain family headquarters for the next several decades.

This Woodlawn house was around the corner from the home that Lucy and John Renz rented and then purchased on Washington Road, where Lucy ran a small grocery in front and John had an upholstery shop in back.

The oldest Cascarano son, Charles, the one who’d urged the family to move to Chicago, worked for the North Shore railroad as a foreman and bought one of the railroad company homes on McKinley, a property that’s still in the family. He was such a good cook that his granddaughter Sue, who was a journalist, wrote an article about the Sunday dinners at his house, where whichever grandchild that had the fortune to be sitting next to grandpa Charles was urged to second and third helpings, regardless of whether they were still hungry. These dinners, Sue wrote, featured “spaghetti or mostaccioli,” and “not pasta,” because “pasta” was a term that “yuppies dreamed up in the 80s.”

Mary Cascarano, who’d been a baby on the voyage from Italy to New Jersey, married Guy Raimondi and raised her family in Chicago. Her husband owned an ice cream cone factory there.

Sadie (whose full name was Santa Domenica) and Anna Mae Cascarano married siblings, Michael and Andrew Tangorra. Sadie lived in Rondout, where her husband worked for the railroad; Anna Mae and Andrew lived on Washington Road, where Andrew was known for keeping a goat.

Nicholas Cascarano became a mechanic for C&S Ford in Lake Forest; when he met his wife Lillian, she was working as a maid at Ferry Hall. Their son Donald Cascarano was one of the first “incubator” babies in the U.S. He and his twin brother Ronald (who did not survive) were born premature in Alice Home Hospital and were rushed by their father along with a police escort to Michael Reese Hospital in Chicago. Don went on to be an art teacher for years at Deerpath School.

Charles Cascarano, who worked for the railroad and was a marvelous cook, was a man of many interests. He raised rabbits in hutches in the back of his garage, and he also began the family tradition of selling Christmas trees on his property. Later, his daughter Sena Rose, and then her daughter Kimberly, continued to sell Christmas Trees each holiday season next to the McKinley Road home.

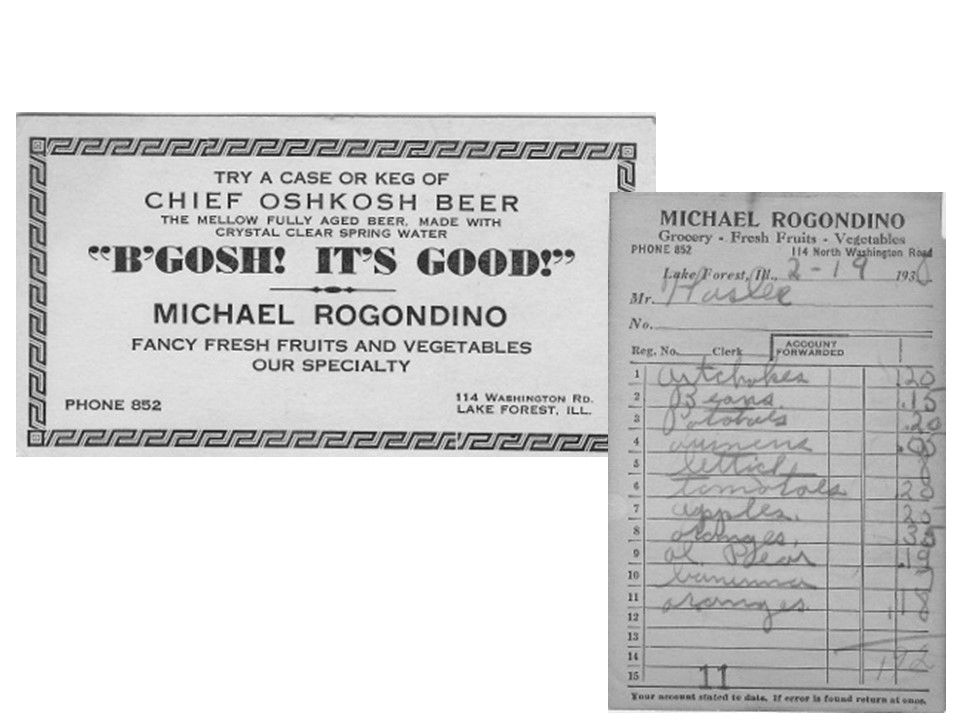

In 1919, Amelia Cascarano married Michael Rogondino, who hailed from the same region of Italy. He had just finished a stint in the U. S. Army for World War I, where he taught several of his fellow Italian-American soldiers how to read and write. After settling down in Lake Forest on Washington Road, Michael started his own business as a produce vendor.

He would deliver fresh produce to homes large and small in Lake Forest and Lake Bluff, building up an enviable list of hundreds of clients. Michael Rogondino was an ambitious man, but unfortunately his success was short-lived. In 1937, he died unexpectedly in the middle of a delivery. His wife Amelia and sons Sam and Anthony tried to keep the business going in the following years, but had to shut it down by 1940. Sam Rogondino did, however, use some of the connections and skills he had acquired later in his career, in his work for Deepfreeze and then S&R TV in Lake Forest.

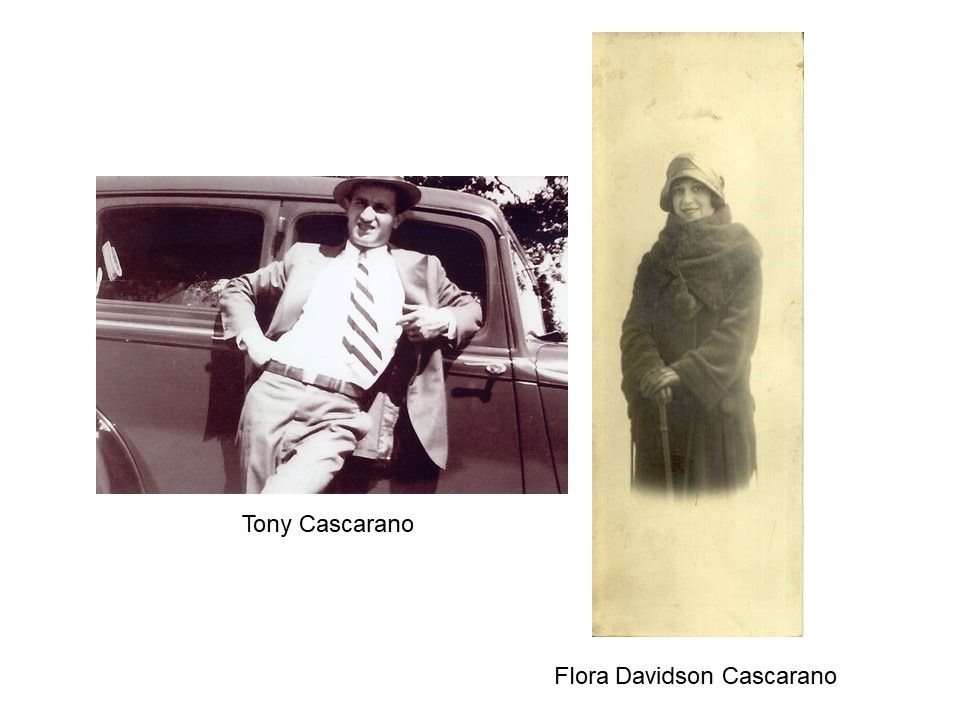

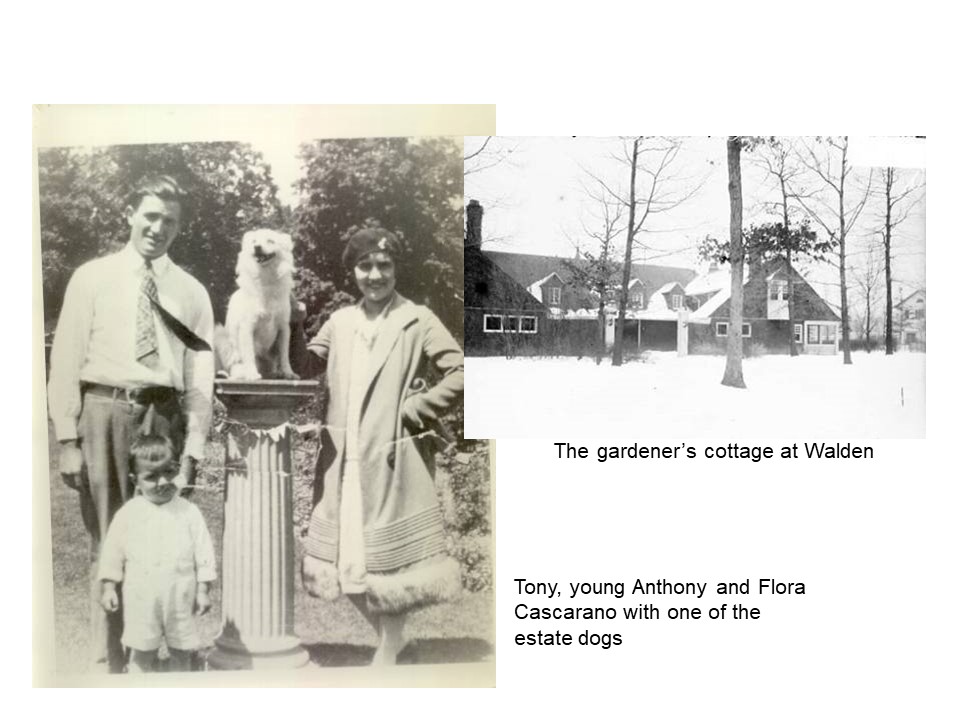

The younger Antonio Cascarano – we’ll call him Tony (there are lots of Antonios and Anthonys in this family) – married Flora Davidson in 1924. Flora was a Scottish immigrant who came to Chicago by way of Canada. She and her sisters were drawn to the area by the abundance of service jobs; when she met Tony Cascarano she was taking care of the children of a Lake Forest family. Tony grew up with the nickname “Skinny,” and he was always the life of the party, very extroverted – both of which you can see in this photo.

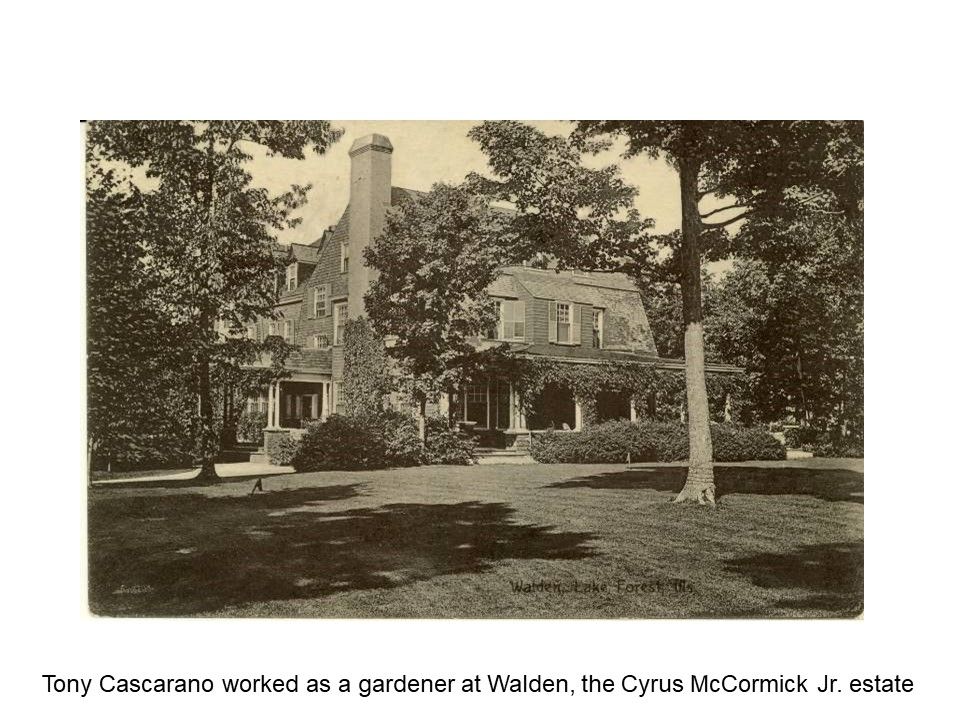

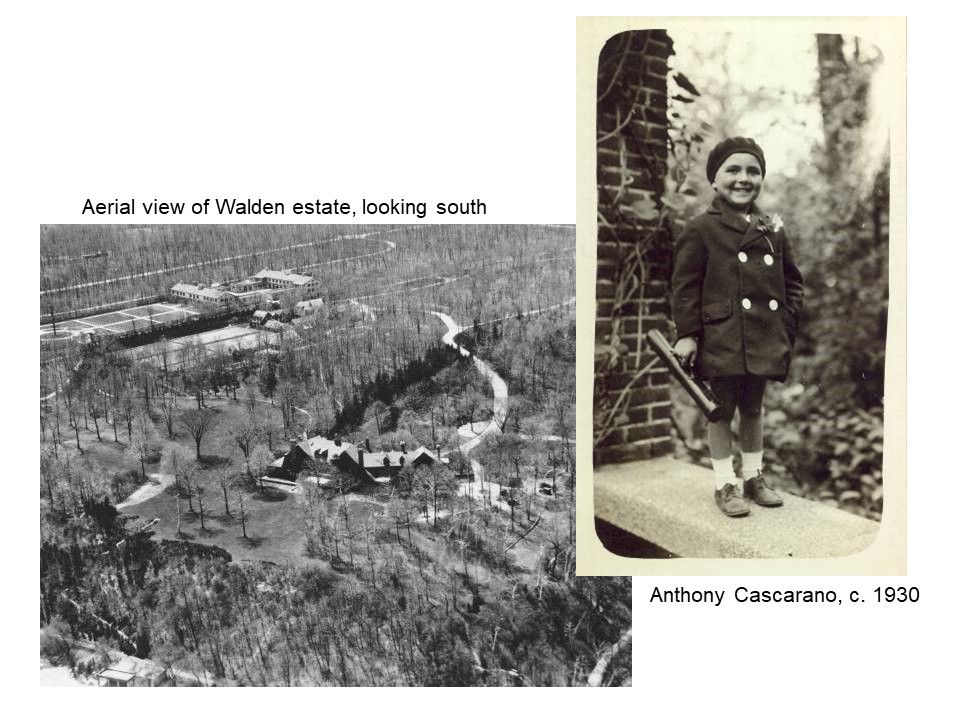

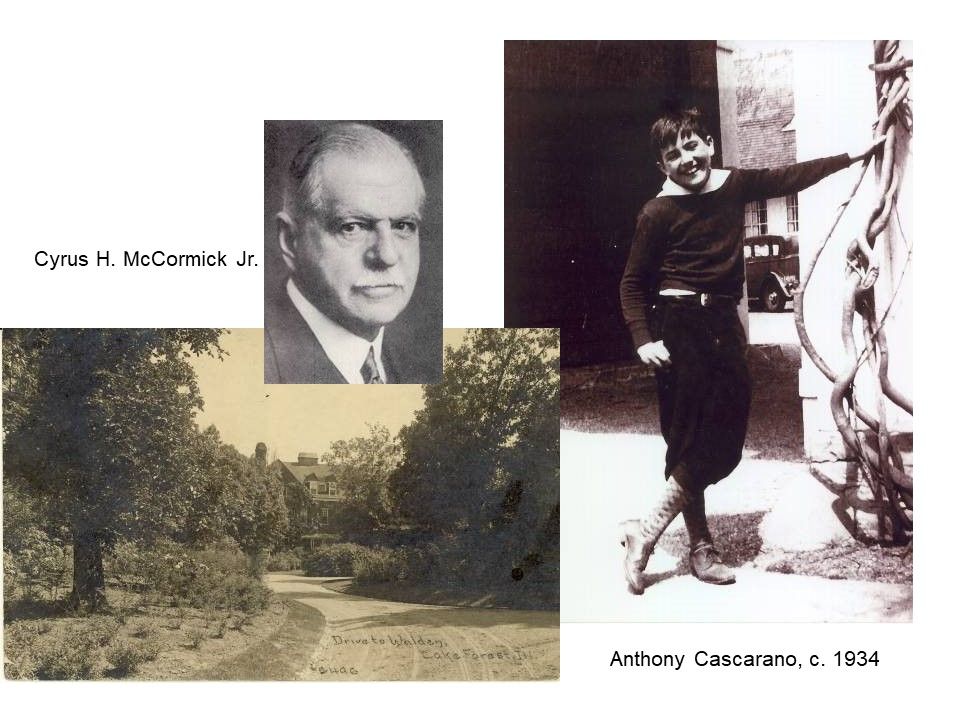

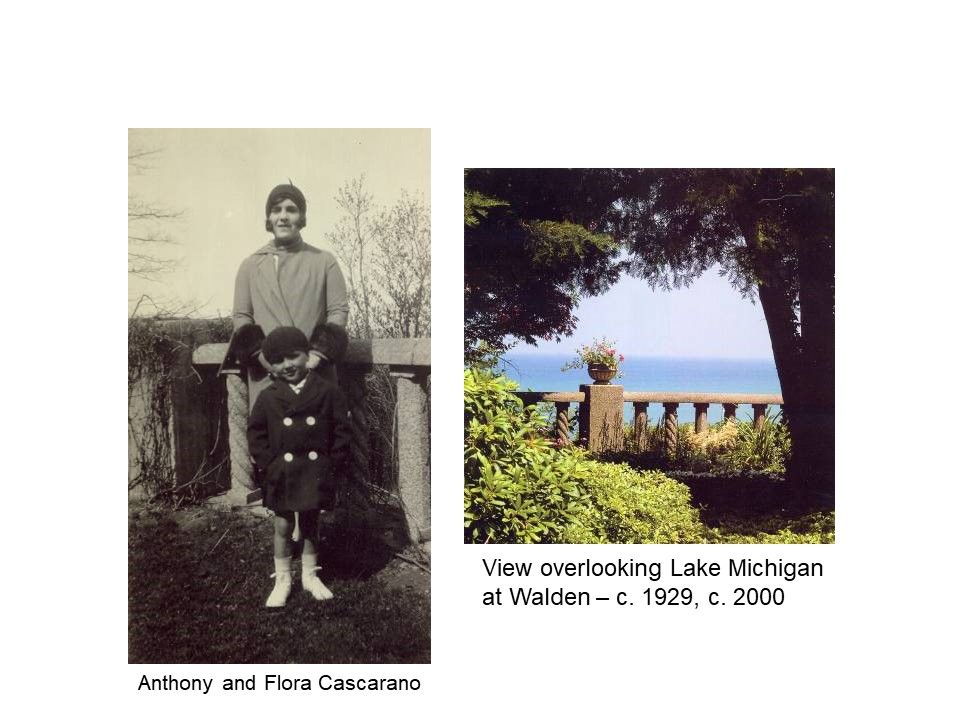

Like his father, Tony Cascarano worked as a gardener. For over a dozen years in the 1920s and 1930s, his job was at Walden, the Cyrus McCormick Jr. home. This 80-acre estate, located at the southeast edge of Lake Forest, had extensive, beautiful gardens.

Tony, Flora and their only child Anthony, born in 1925, lived in the gardener’s cottage at Walden. They resided in an apartment on the main level, with one of the chauffeurs and his family living upstairs – although in the winter, the chauffeur would move with the McCormicks to their Burton Place home in Chicago, so the Cascaranos would then have the house to themselves.

Anthony remembers life at Walden being a bit like the TV show “Upstairs/Downstairs.” The service staff and their families all lived on the grounds and called the main residence “The Big House.” The estate was its own little community, with Scandinavian maids and farm workers, Italian gardeners, and a very British butler.

The Walden estate held all sorts of possibilities for a small child. Young Anthony Cascarano would hang out in the farm fields, located near the Westleigh road entrance, and learn how to milk the Guernsey cows from the farm superintendent. The McCormicks often travelled, and when they weren’t in residence, the families of the estate workers would have fresh bottled milk and vegetables delivered to their door from the farm and vegetable gardens.

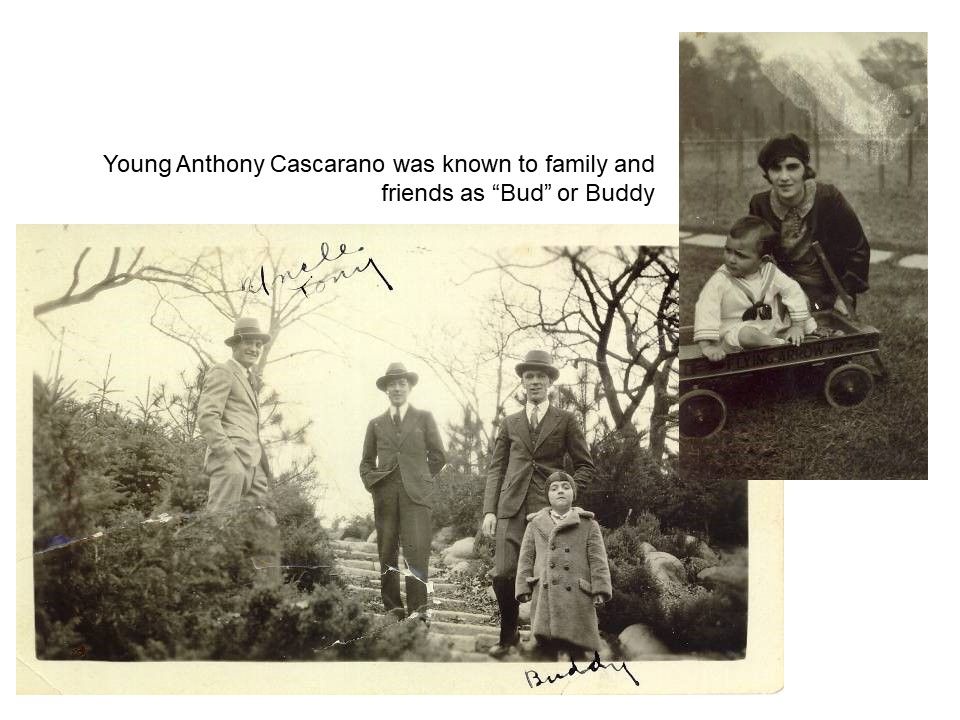

Anthony was known to family and friends as “Bud” or Buddy. (His father, grandfather and at least three of his cousins were also Antonios or Tonys, so nicknames were extra important) He loved to play in the estate’s majestic ravines, which he knew like the back of his hand. Occasionally – when they could find him – Anthony might be asked to assist his parents with their work in the estate gardens as well.

When the McCormicks did come to stay at Walden, the estate children were warned to stick close to home. Mr. McCormick would be driven on tours of his estate, to check that the farm and gardens were running smoothly. Anthony vaguely remembers once, when he was six or so, playing in his front yard and being struck speechless by a big, red-faced man who said, “Oh, you must be little Tony!”

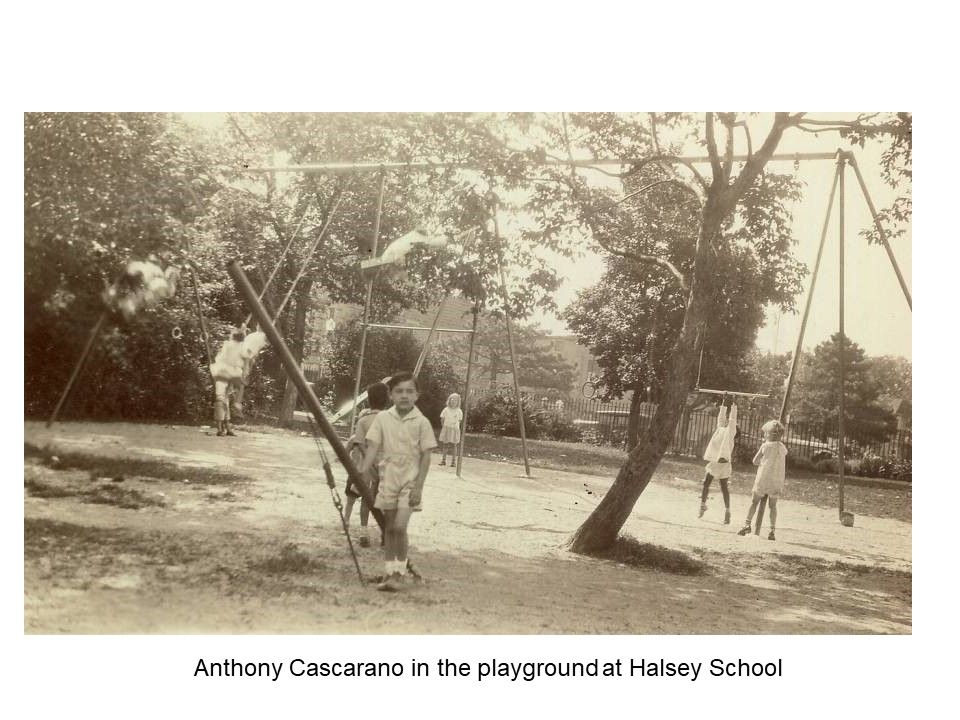

To get to school, even in the 1930s, Anthony used the classic method: the parent carpool. The young children of the estate would all ride together up to Halsey school in the mornings, with one of the chauffeurs dropping them off.

Even though Anthony was an only child, he always had lots of playmates, either on the estate or amongst his extended family. He had dozens and dozens of cousins, some so much older than him that he thought they were aunts when he was little. A lot of the Cascarano and Rogondino and Tangorra cousins lived up on Washington Road, and he would ride his bicycle up to visit them. If one family happened to be out, well, he’d just move on and try the next house, and the next, till he found someone to play with.

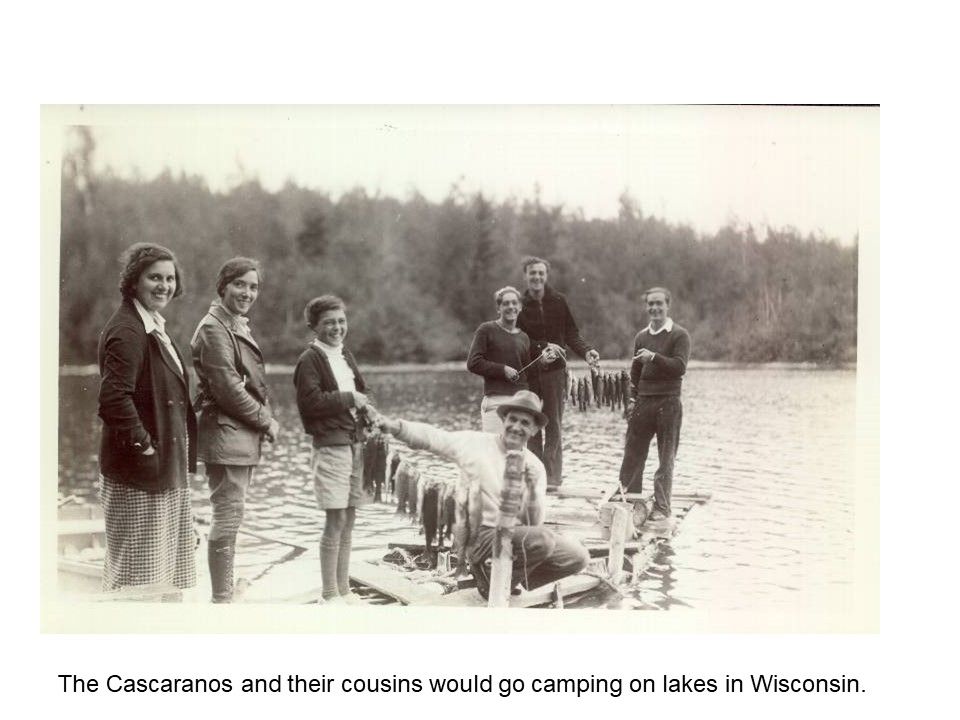

In the summers, Tony and Flora and Anthony would drive up to the lakes in Wisconsin, where they would camp and fish. Here you see them with Flora’s sister Belle and Anthony’s Raimondi cousins from Chicago, celebrating a prolific catch.

Not long after Cyrus McCormick Jr. died in 1936, his wife decided not to continue running the estate, and the Cascaranos moved to a home on Telegraph Road in west Lake Forest. Tony got a new job maintaining the buildings at Barat College, and would take Anthony up to high school in the mornings before work.

Walden, as with many large estates in those decades of high property taxes and changing modes of living, was eventually subdivided. The main house was pulled down in 1956, along with its fellow former McCormick estate to the south, Villa Turicum. A few features remain, however, such as the Ravello and lake overlooks, as can be seen in these two photos.

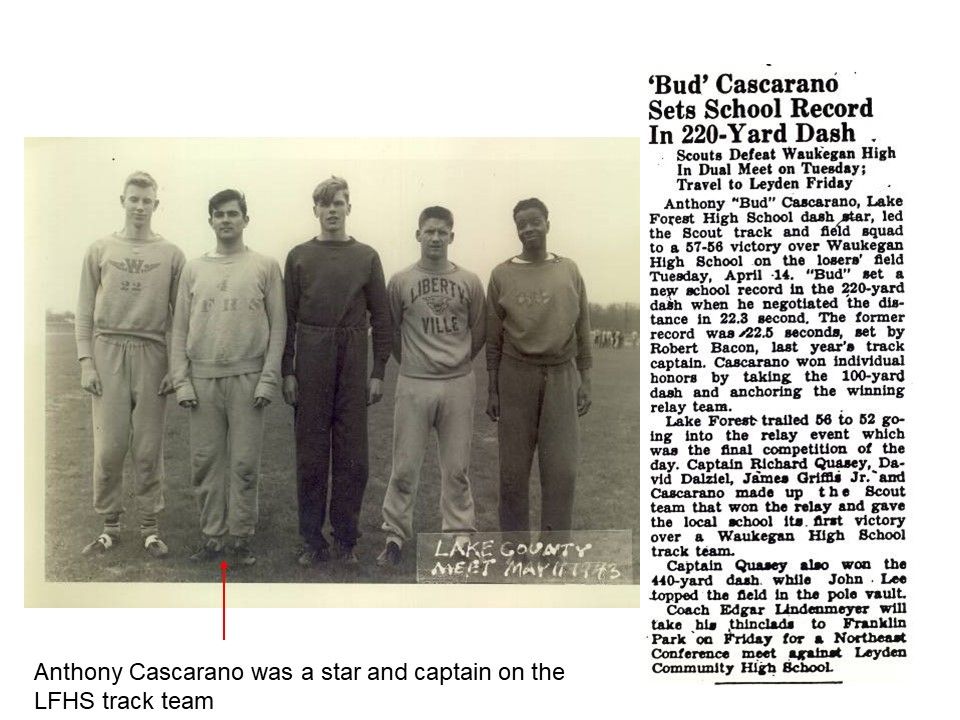

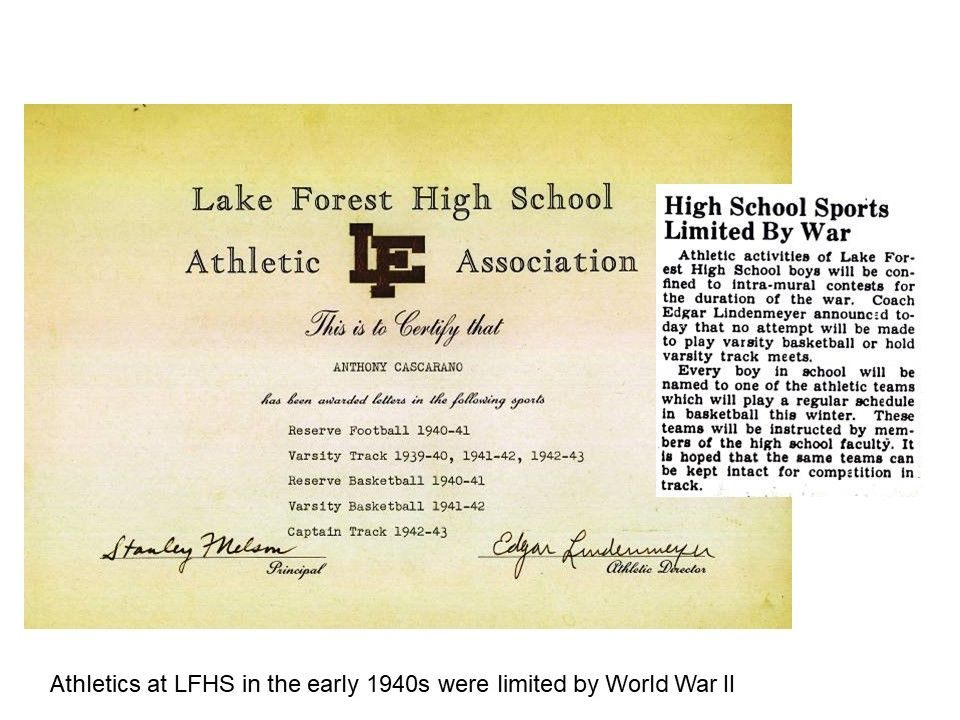

Anthony Cascarano was an active participant in Lake Forest High School activities. He was in the band and played football and basketball. But what he was best at was track and field. In 1943, he set a school record in the 220-yard dash, completing the race in 22.3 seconds. He also ran the 100-yard dash and the relays, and was elected captain of the team, which was coached by Edgar Lindenmeyer.

Looking back on his track experiences, Anthony Cascarano is a bit self-deprecating. Lake Forest was good in its own conference, he says, but when they went down to Chicago to face the runners from the city schools, “those kids would leave me in the dust.” At that time, the training for the track team wasn’t particularly rigorous. Anthony would sometimes get a ride with a fellow from the maintenance crew at the high school who was from Sweden, where they were serious about their track and field. He used to scoff at the school’s training regimen, which was basically “buy yourself a pair of track shoes with spikes on it” and start running.

Of course, at that time in the early 1940s, high school sports were not at the forefront of people’s minds, and their schedules and training were curtailed by World War II. Anthony Cascarano remembers that when they had away meets at Highland Park, because of gasoline rationing for the war, the 30-member track team would take the North Shore Line, with all of their track equipment in tow. Some mischievous kids would always get out the shot put and let it roll up and down the aisle, like a pinball machine.

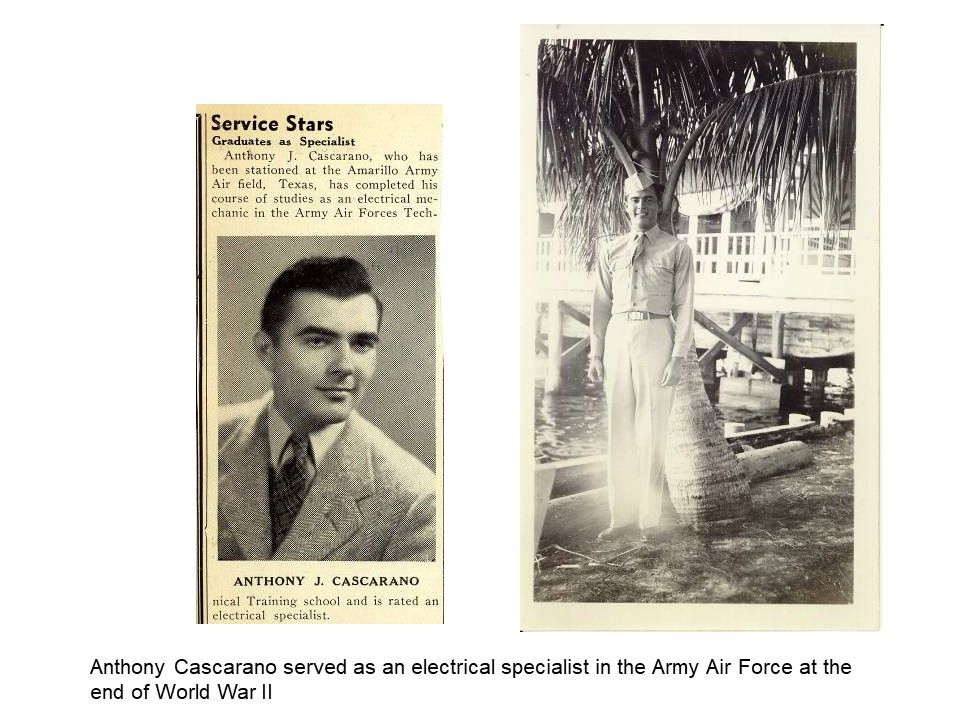

After graduating from high school, Anthony Cascarano, like many men of his generation, entered the armed forces. By 1944, he was training to be an electrical specialist in the Army Air Force, a technical position that took him from Florida to Michigan to New Mexico to Texas, for various instruction and field schools. He started his training at Miami Beach, where the Air Force bought out nearly every hotel and turned them into barracks. Anthony remembers that there were still some residents of the hotels around, older women who’d lived there a long time, and when the recruits would go out on the beach to do their P.T. regimen, these little old ladies would don their bathing suits and join them, to get some exercise.

The end goal of all his training was to become part of a B-29 bomber crew, an electrical specialist for a very futuristic, remote control operated plane. By the time these crews were trained and put together, however, the war had ended.

While training in Albuquerque, during his downtime Anthony would often go down to the base library to read. One of the more useful books he encountered there was a volume that contained detailed descriptions of various career choices. He flipped the book open one day to the pages about “Industrial Design,” and his career path was assured. When he returned home after the war, Anthony enrolled at the Art Institute, which had just begun to offer that course of study.

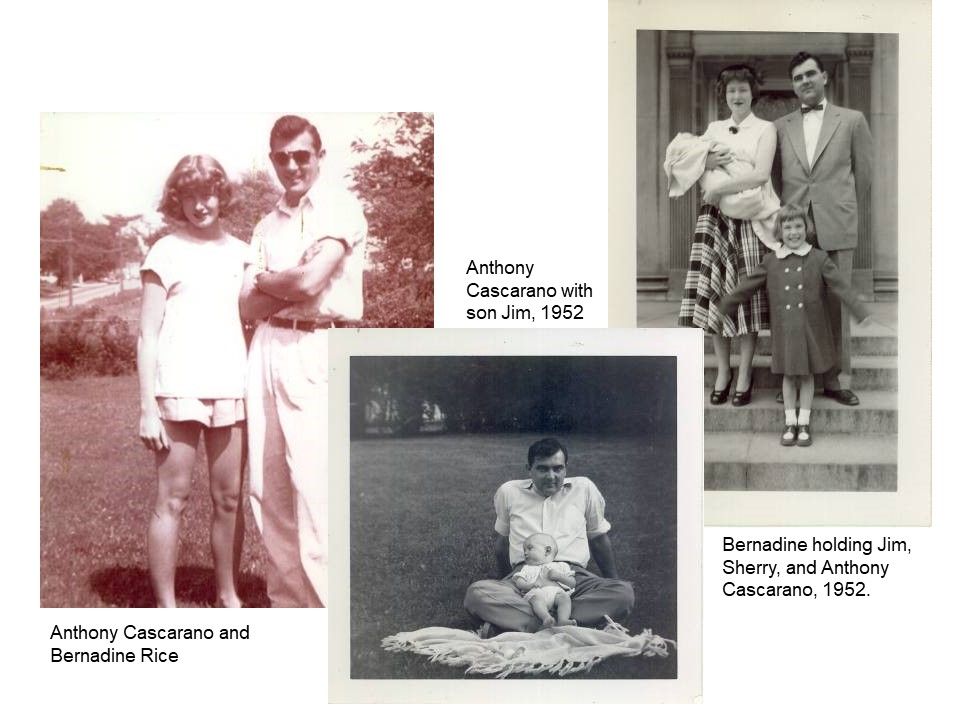

It was while he was attending school that Anthony Cascarano met Bernadine Rice, who was from Waukegan. They were both on the train, the only two people in the car. His opening line was a classic: “Is this seat taken?”

They were married shortly thereafter. Following a brief stint in Dearborn, where Anthony worked for Ford Motor Company, the Cascaranos returned to the Chicago area with their now family of four. Anthony got a job with International Harvester Company designing tractors and trucks. And he got it without mentioning in his interview the fact that he’d met International Harvester president Cyrus McCormick as a child.

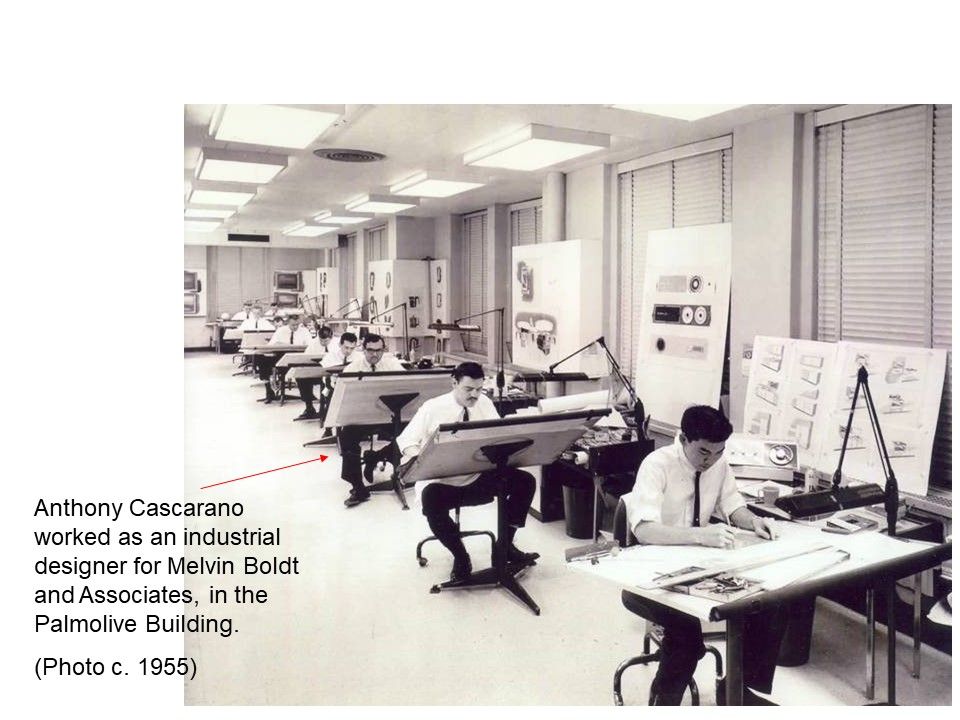

At the time, International Harvester had few competitors for its products, which meant there wasn’t much scope for imagination for a creative designer: they did not have to change their designs very often. Anthony Cascarano moved to another firm, Melvin Boldt and Associates, which was located at the Palmolive Building in Chicago. There, he worked on lots of new products: Zenith table model radios, jukeboxes, televisions, and kitchen appliances of all kinds until his retirement in 1980.

Upon returning to live amongst aunts and uncles and cousins in Lake Forest, the Cascaranos built a house on Ahwahnee Lane, where they’ve lived for over 50 years. Bernadine Cascarano started her own sewing business – creating drapes, needlepoint pillows, and other household items.

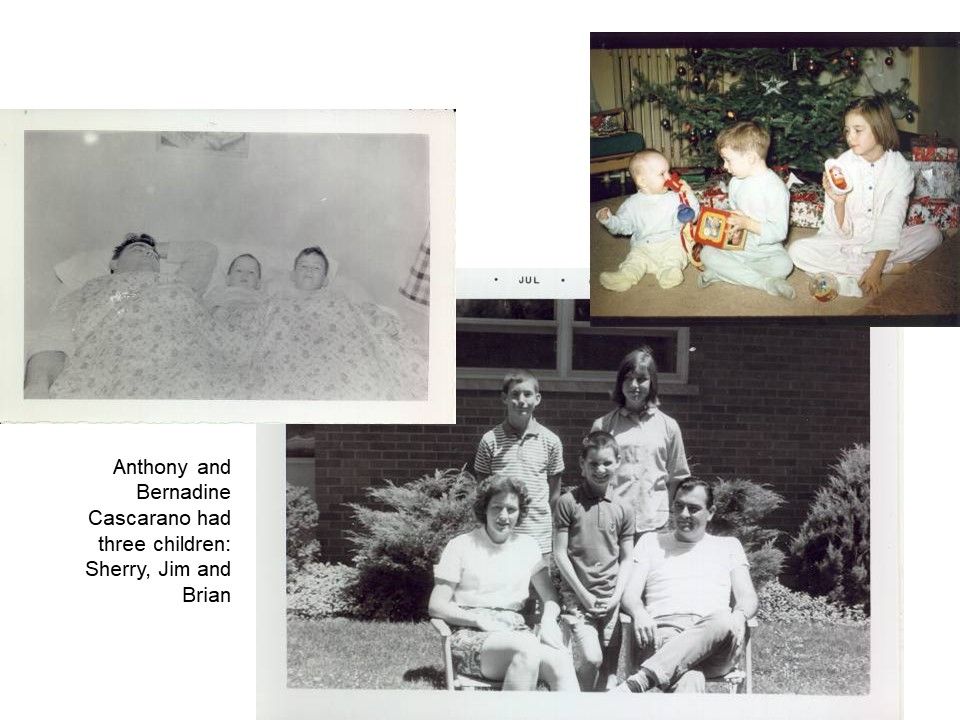

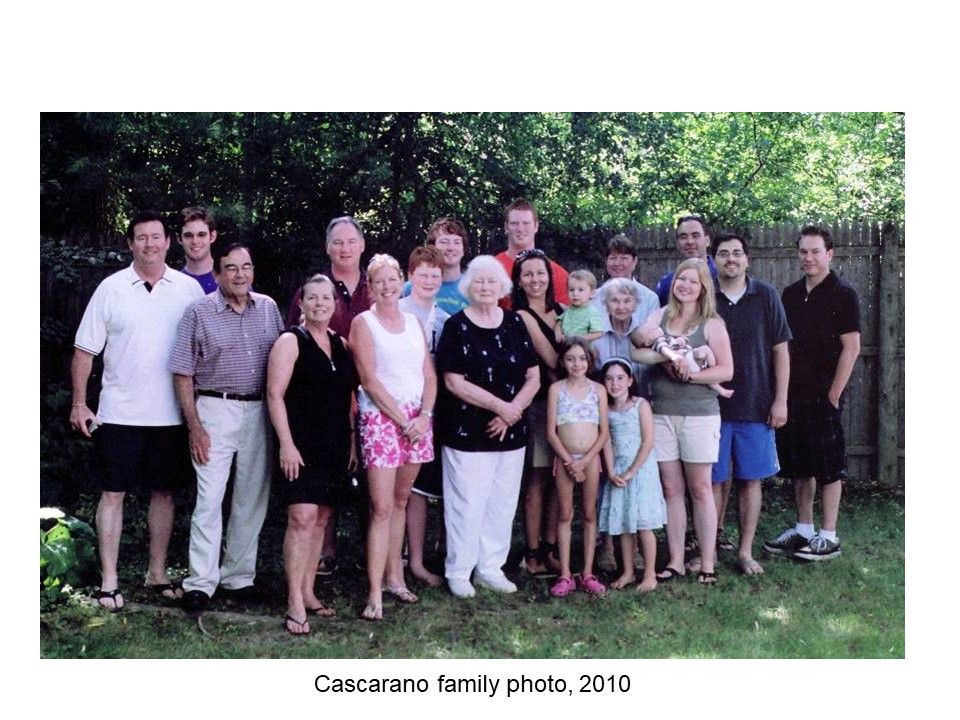

Their three children, Sherry, Jim and Brian, grew up attending Lake Forest schools and have all settled in the North Shore area themselves, making family reunions like the one pictured here not uncommon. Although Lake Forest is no longer a village of the 80-acre estates where his father and grandfather tended gardens, it’s turned into a very attractive city that Anthony Cascarano considers the only place to live.