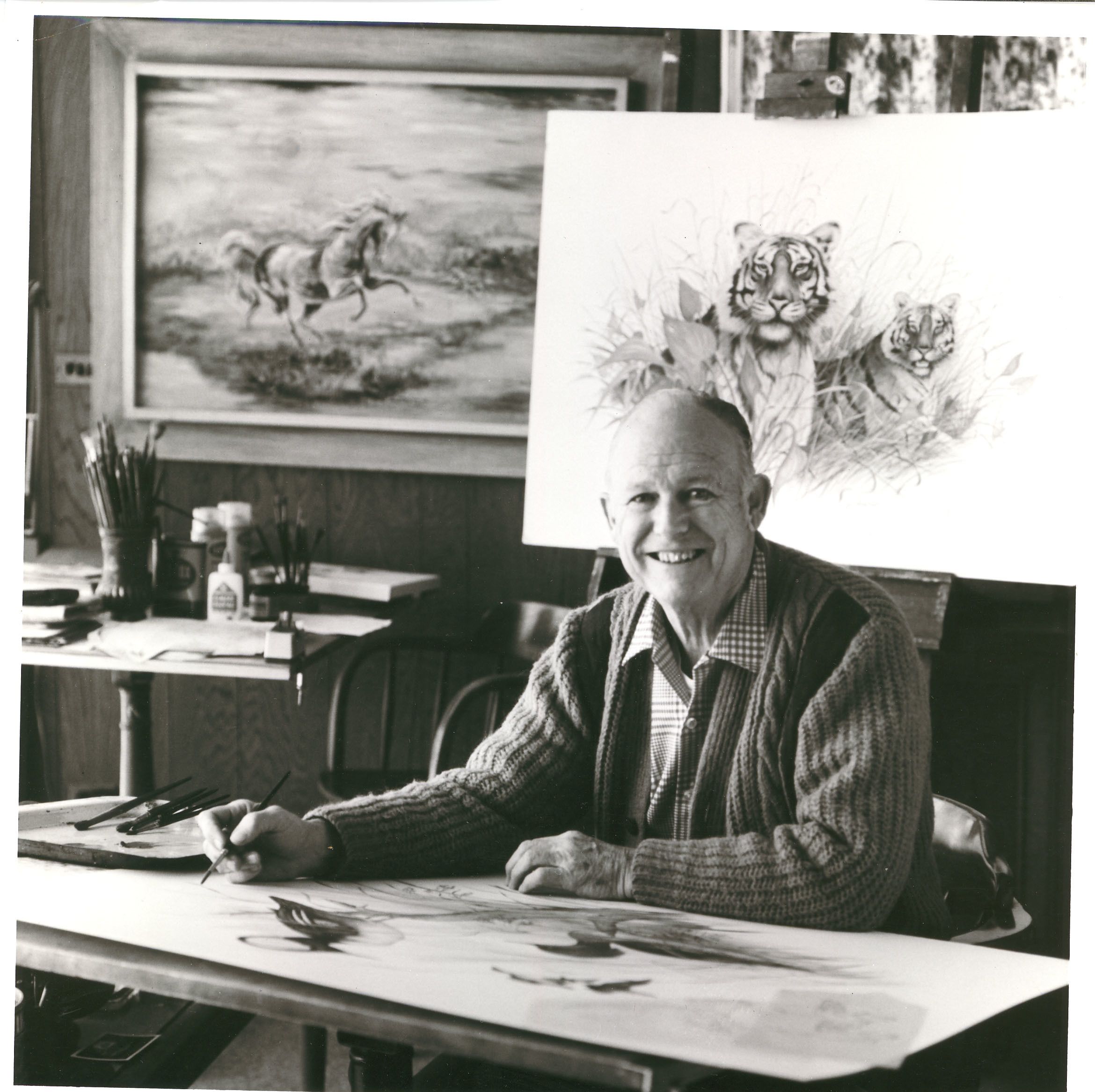

James Leland Lockhart: "The Twentieth-Century Audubon"

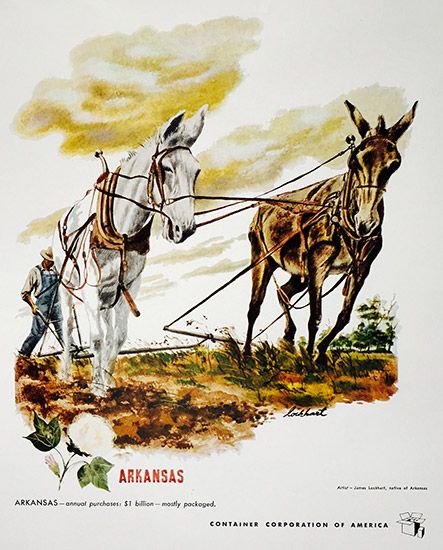

James Leland Lockhart (1912-2005) was one of America's foremost nature and wildlife artists. Growing up in rural Arkansas along the Mississippi River, his careful observation of the natural world began at an early age. “I knew almost every plant, bird and animal in those parts,” he said, having grown up with “a rifle in one hand and a fishing pole in the other.”

Though absorbed by drawing since receiving his first box of crayons at age four, James Lockhart never considered art as a profession until midway through his studies at University of Arkansas, when his role as art editor of the yearbook took precedence over his architecture coursework.

His father Leland Lockhart, a railroad engineer, worried about the viability of an art career during the Great Depression, and insisted his son work for a year before changing course. So James Lockhart took on a job drawing cotton acreage maps in 1933 through a New Deal program. Ironically, a chance doodle, drawn from a news article about President Roosevelt, served to cement his new direction: Lockhart’s supervisor sent it to the White House, and Lockhart received a handwritten response from the President encouraging him to pursue his artistic ambitions.

In 1934, James Lockhart ventured north to Chicago to train at the American Academy of Art; he also took night classes at the Art Institute. His first big break came when, as an apprentice for a Chicago art studio, he ran some ads over to the agency that had the Wrigley account. Noticing a few mistakes, the account executive told Lockhart to take them back for corrections. “I can fix that,” he told her. “It’s so simple, let me do it right here.” Impressed with his facility and initiative, she later called him up for a job.

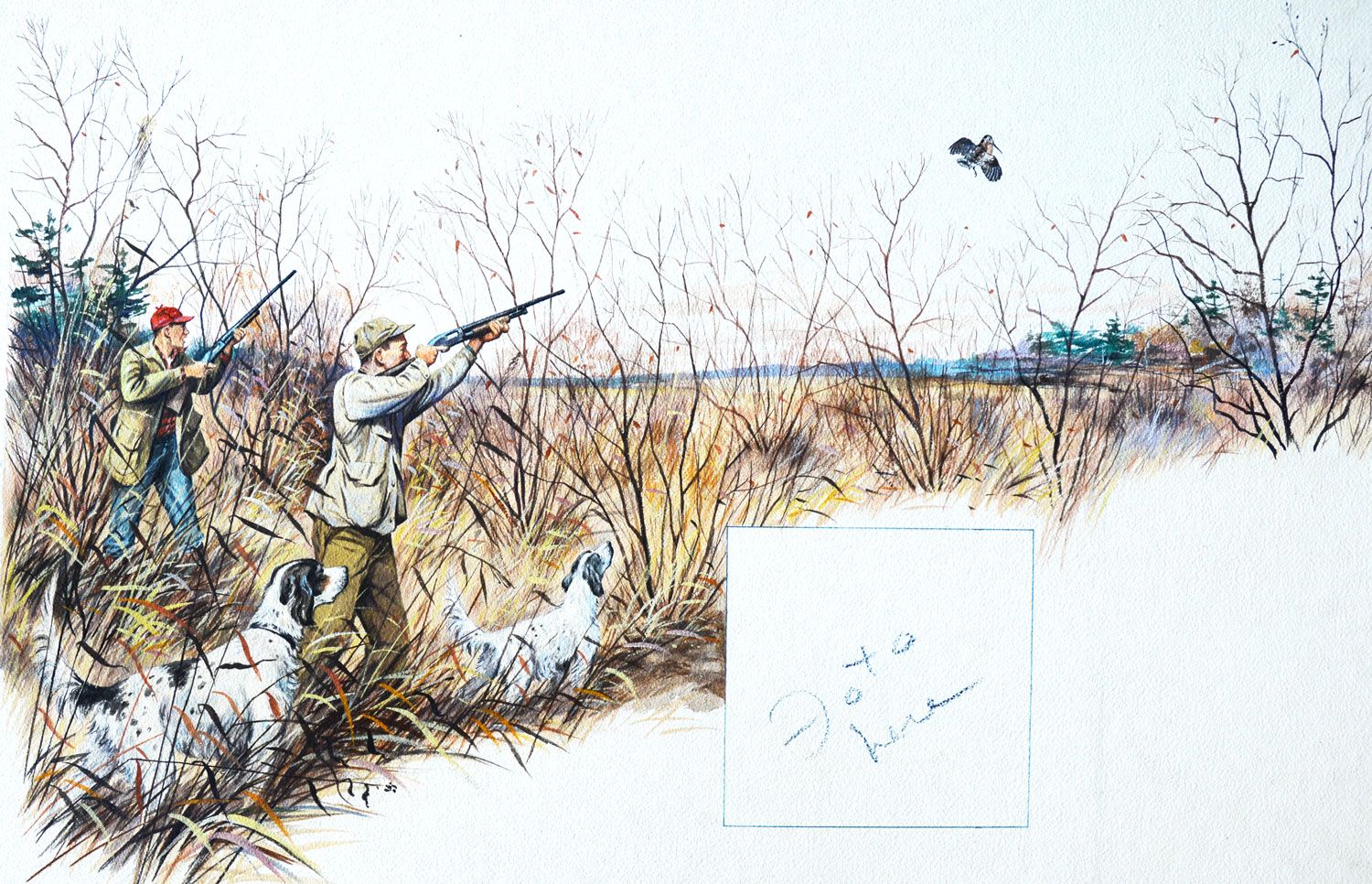

This led to other assignments, both advertisements and illustrations, that featured in magazines like Coronet, Collier’s, Sports Afield, Country Gentleman, and Saturday Evening Post. World War II brought a crucial role for Lockhart’s talents – with full-time security guards posted at his studio, he illustrated flight manuals for new military planes.

After the war, James Lockhart’s career gradually shifted focus. He began drawing animals in the background of his commercial work, and soon requests piled in for all sorts of wildlife. Publishers and collectors clamored for his sporting pictures, portraits of champion field dogs, and series of game birds. Soon his brush became an important advocate for the preservation and protection of nature’s wonder.

In the early 1950s, Lockhart and his family moved to Lake Forest, building a house on Walden Lane, where “my first nature painting was born,” he wrote. “It is only a few steps from my studio to the ravine. Carved out by the glacier ice eons ago, this deep ravine and its twisting creek have been my inspiration.”

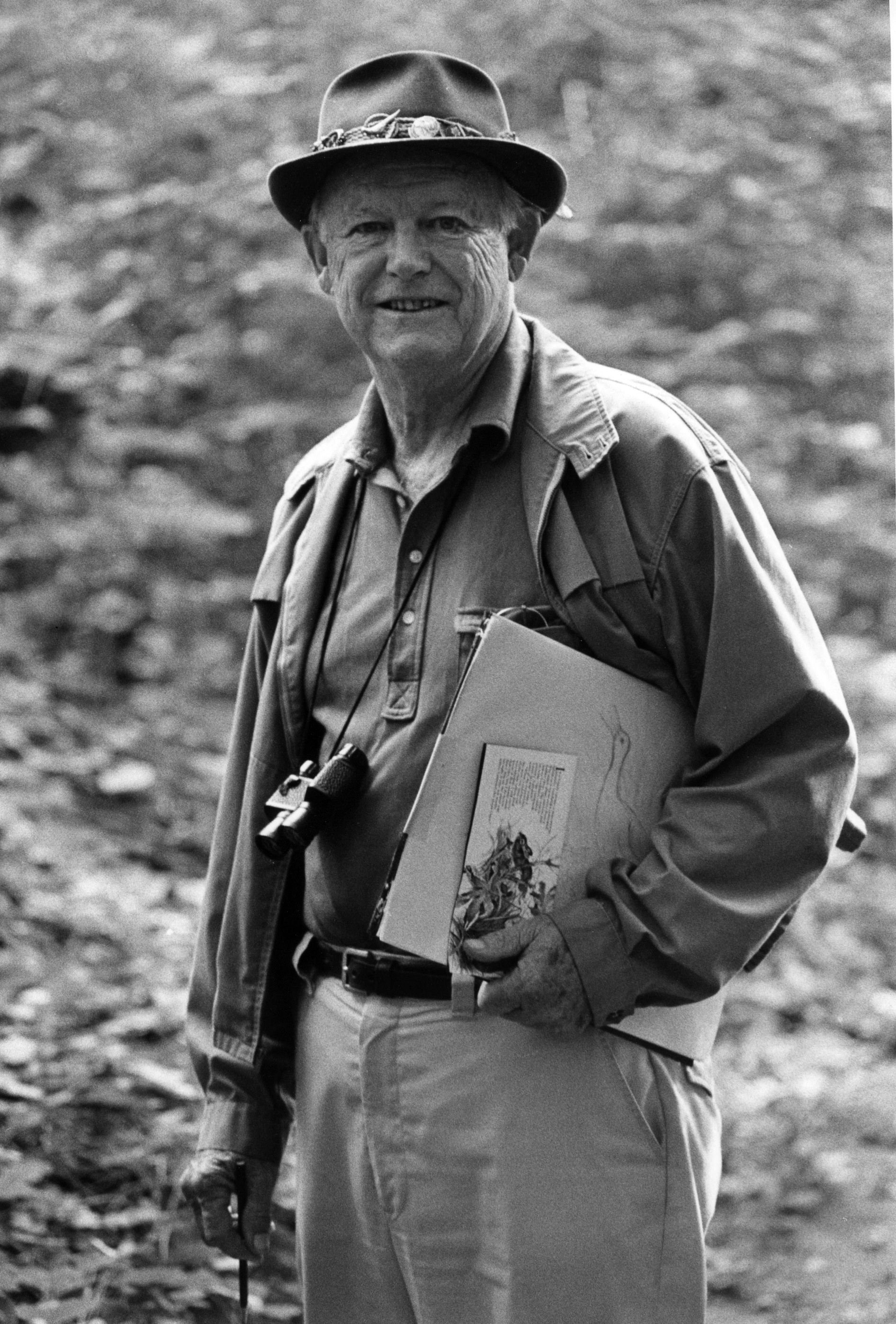

Lockhart’s art depicted a range of species who had been affected by habitat destruction, breeding ground fragmentation, overhunting, and contamination through pollution. Lockhart worked to depict the breadth of duck species on multiple assignments. As a trustee for Ducks Unlimited, Inc., he spearheaded efforts to drive awareness of the need to preserve the diverse populations. Lockhart gave the organization the rights to sell limited-edition art prints of his work in 1971, which brought in more than $150,000 for Ducks Unlimited.

Lockhart was a staunch advocate of conservation efforts, both for land and animal protection. He remained involved in the Lake Forest Open Lands Association from its founding in 1967 until his death in 2005 at the age of 92. He also supported The International Crane Foundation and The Nature Conservancy. He published two books, Portraits of Nature and Wild America, showcasing the diversity of species in North America.

The cover of Lockhart’s 1967 monograph Portraits of Nature featured a sublime depiction of the bald eagle in its natural habitat. “Emblem of our nation, personifying freedom and liberty, it is ironic that this majestic bird is fighting for his right to survive.” Lockhart wrote. “The bald eagle needs our help.”

The beauty of the book’s imagery and the passion of its conservation narrative vaulted the volume to great heights. In 1968, the White House was gifted a copy of Portraits of Nature by Connecticut Senator William Benton, publisher of Encyclopedia Britannica. Lady Bird Johnson called it “an absolutely dreamy book” and gave it a place of prominence on the table in the West Hall of the White House, where guests could see and peruse it.

At the time, the idea of Lockhart donating the original painting to the White House was broached, but they discovered that artists had to be deceased for 20 years in order for their work to enter the permanent collection. The Lockharts did not feel sanguine enough about the prospects of Democratic candidate Hubert Humphrey to donate it to his personal collection instead, and so the eagle did not go to Washington.

At least, not yet. In the 1970s, Pickard China created a special edition collector’s plate featuring the bald eagle. Illinois State Senator John Conolly presented President Gerald Ford with plate number one in 1974.

Throughout his long career, Lockhart earned many national awards and recognitions. He won the National Graphic Arts Award in 1968 and 1970 and the Printing Industry Award in 1970 and 1971. He was named Illinois Artist of the Year in 1992. A display of his work was held at Chicago’s prestigious Field Museum of Natural History in 2002, the only time that museum had honored a living artist.