Once upon a golf links: Mason Phelps, Marion Phelps Pawlick and the Phelps Family in Lake Forest

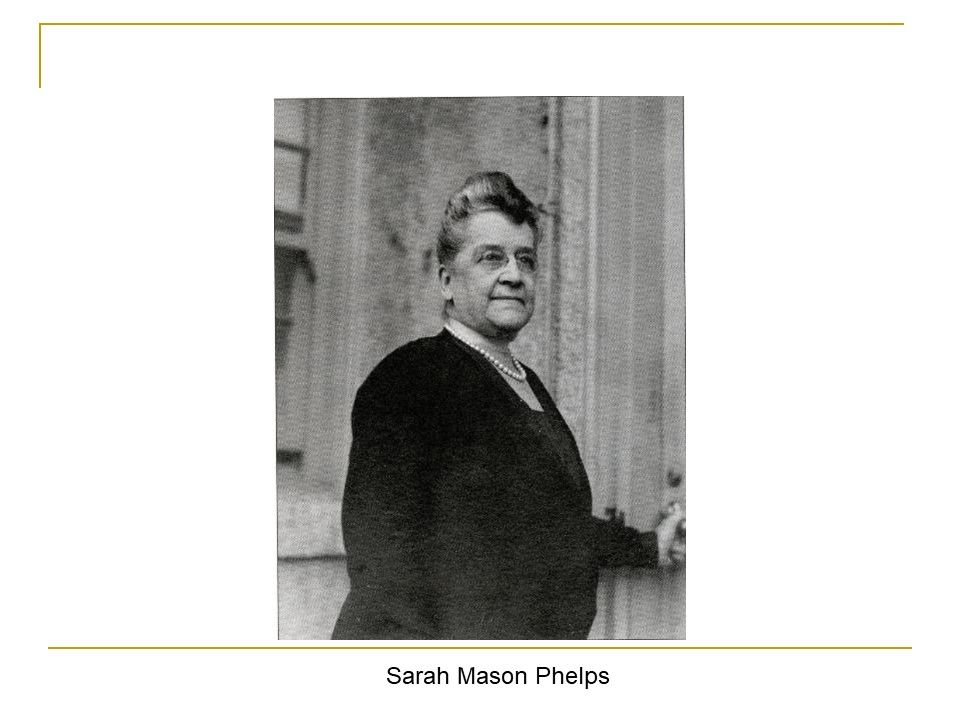

The local story of the Phelps family begins with Mason Phelps. He was born in 1885 in Milwaukee to Elliott Hubbard Phelps and Sarah Mason Phelps. His father, Elliott, was a grain broker who lost heavily in the crash of 1885. He died when Mason was a boy. It was his mother, Sarah, who was most influential in his life. She became a Certified Public Accountant (CPA), highly unusual for a woman at the time. Many who went to her for bookkeeping had no idea they were working with a woman.

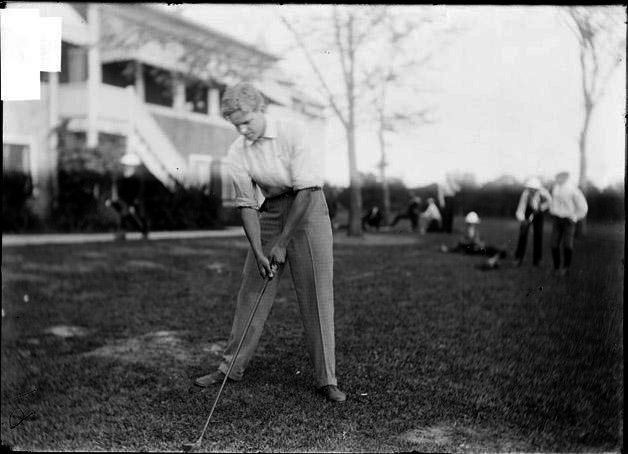

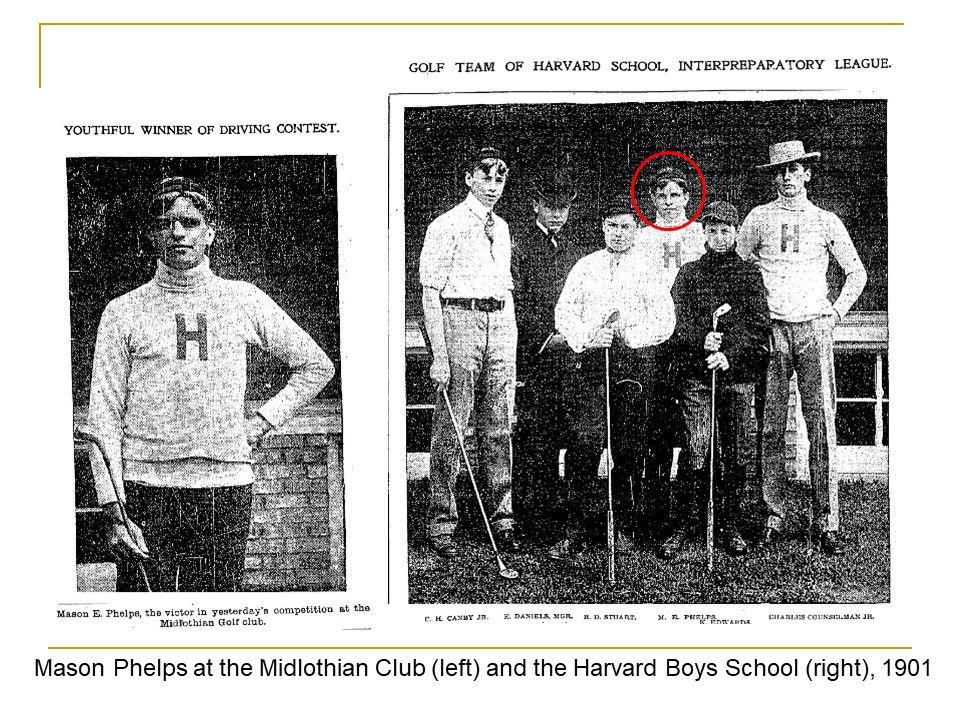

Around 1890, the family moved to Prairie Avenue on the south side of Chicago. Young Mason attended the Harvard Boys School. Around this time, the late 1890s, the game of golf was starting to explode in Chicago, the city which really introduced the game to much of the rest of the country. Mason started as a caddy on the local golf course, the Midlothian Club, which was founded in 1898, and quickly exhibited a preternatural talent. He won a driving contest at Midlothian in 1901, and was a member of the Harvard School’s golf team, along with his classmate and friend, R. Douglas Stuart.

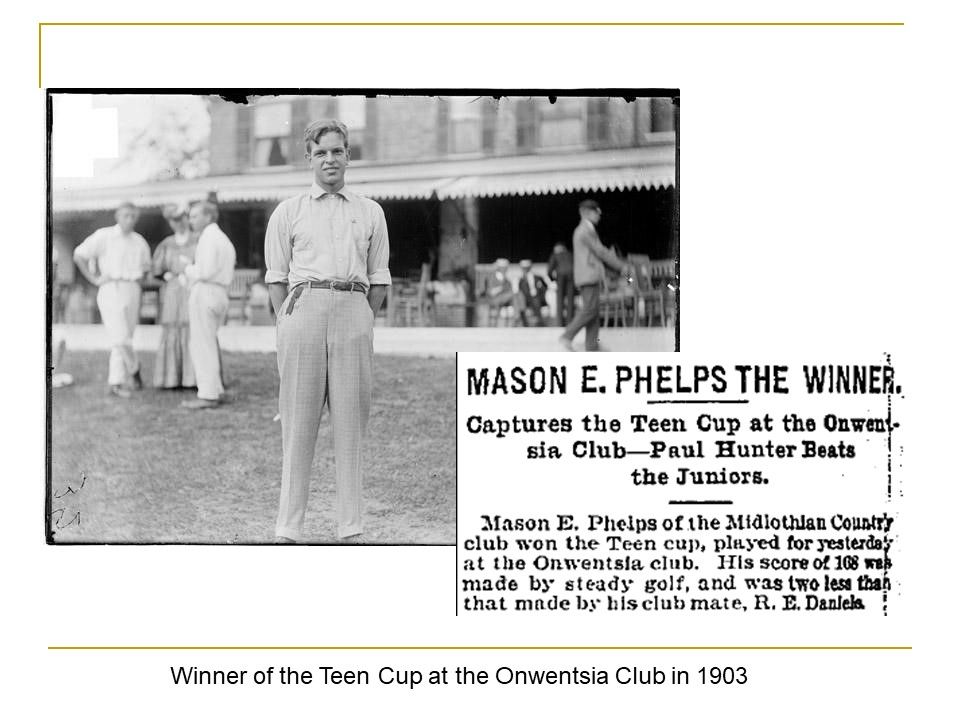

Mason Phelps next went on to the Hill School in Pennsylvania, where he continued to star on the school golf team. During the summers, it was golf that first took him up to Lake Forest, when in 1903 he competed in Teen Cup at the Onwentsia Club and won, with a score of 108. After the Hill School, Phelps attended Yale University on a full scholarship, enrolling in the Sheffield Scientific School. He was a member of the golf team at Yale, serving as captain his senior year in 1906.

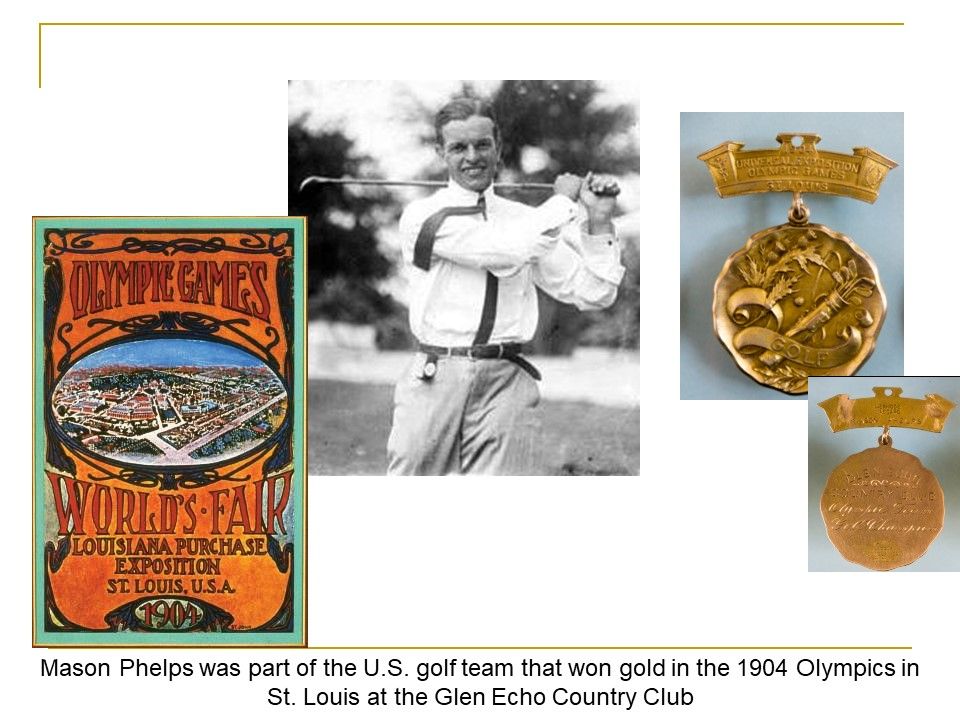

In 1904, Mason Phelps’ ability on the links brought him an exceptional opportunity: a chance to compete in the Olympics. The Paris games in 1900 had featured golf as an individual event and with the 1904 Olympics being held in St. Louis, near the center of the Midwestern golfing boom, a team competition was added. The Glen Echo Country Club hosted the event. The U.S. entered more than one team - Mason Phelps competed on the Western Golf Association team, featuring ten of the best amateurs from the clubs around Chicago. The team competition featured 36 holes of stroke play, and the Western Golf Association team took the gold medal with 1,746 strokes – you can see that golf medal pictured here. Phelps finished 15th overall. In the individual competition, he finished sixth in qualification and was eliminated in the quarterfinals of match play.

Infighting over player eligibility requirements prevented golf from being part of the 1908 London Olympics, where it might have been expected to thrive. After that, golf was not again included in the Olympic Games until 112 years later, in Rio 2016.

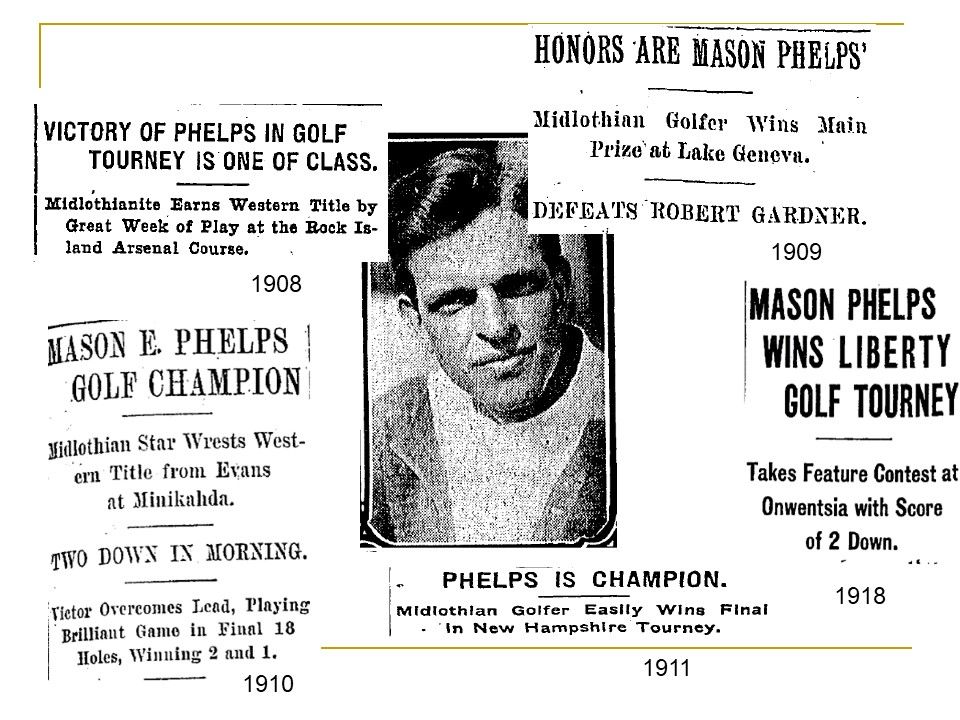

After graduating from Yale in 1906, Mason Phelps continued to compete in golf tournaments, both in the Chicago area and across the country. In 1908 and 1910, he won the Western Amateur tournament, defeating top amateurs from around the world. His daughter Marian recalls that, many years later, there were so many cups and trophies around the house that the family ended up using them as pitchers and containers. His championships at various courses across the U.S. gave him victor’s privileges at the various clubs, a legacy which passed down to his children, who found they were able to play at private clubs from California to Michigan and elsewhere on their father’s laurels.

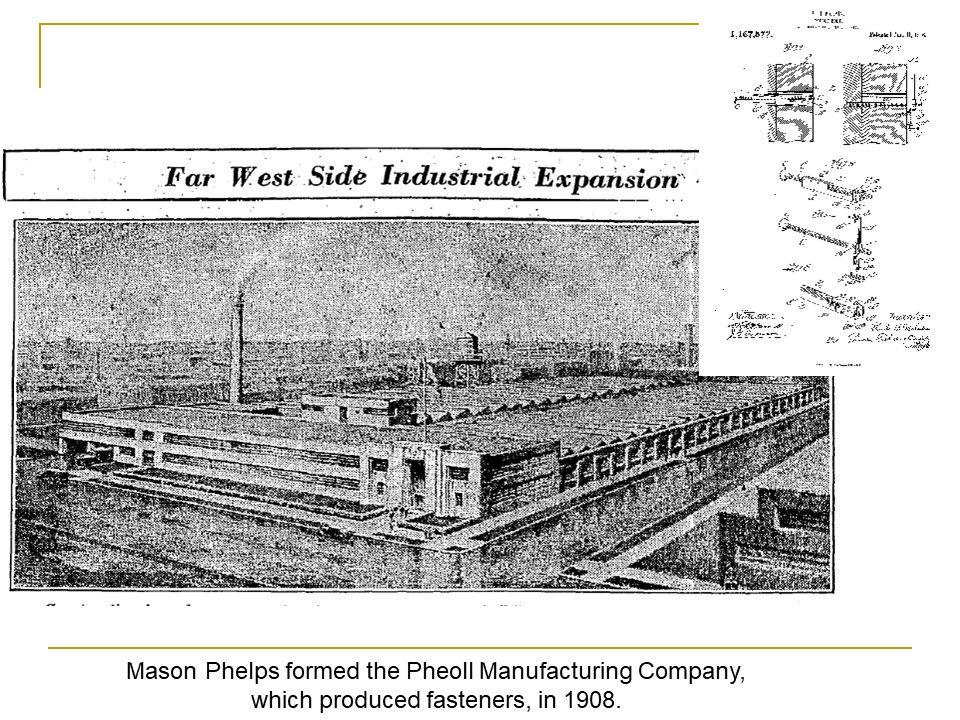

In his travels after graduation, Mason Phelps became interested in the machinery used to fabricate fasteners like nuts and bolts. He had an idea of a single machine that might take the place of two others. It was through connections forged on the golf course that he was able to give this idea a proper start. He went to Silas Strawn, of the law firm Winston & Strawn, who was a friend and USGA official, for a loan of $30,000, which he used to form his first small machine shop, above a saloon on Cicero Avenue in Chicago. Beginning with this idea, which was patented, and other subsequent inventions, and augmented by his mother the CPA’s financial skills, Mason Phelps formed Pheoll Manufacturing Company, which provided fasteners largely for the automotive industry. Soon he was able to open a plant at 6300 Roosevelt Road, pictured here.

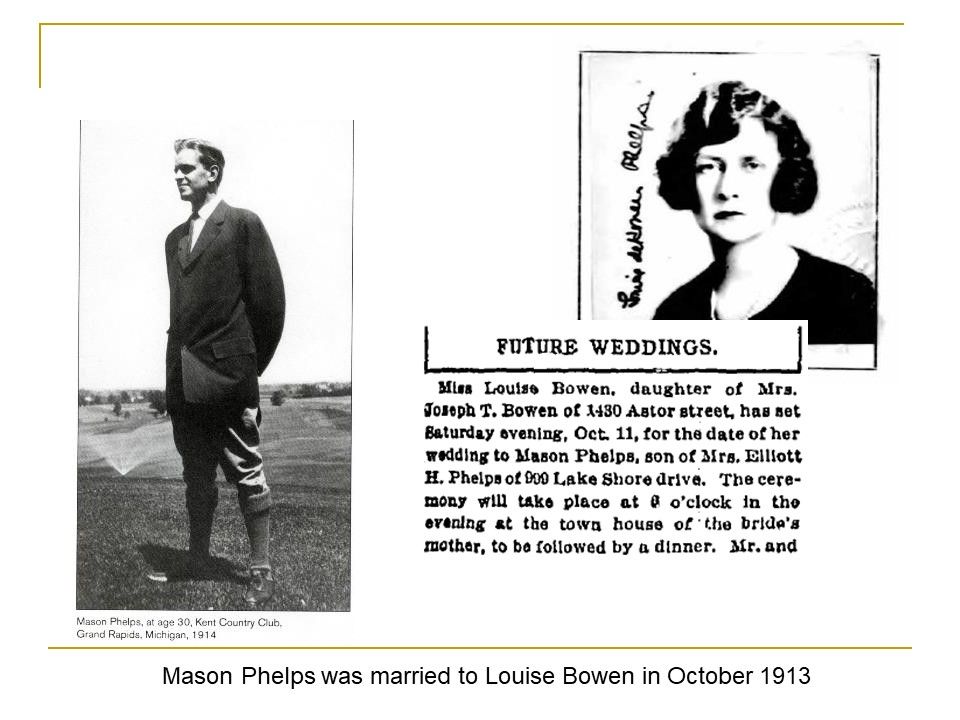

In 1913, Mason Phelps was married to Louise Bowen, daughter of Louise de Koven Bowen, the social reformer and suffragette. This marriage did not last, and in 1921 Louise went to Reno for a divorce.

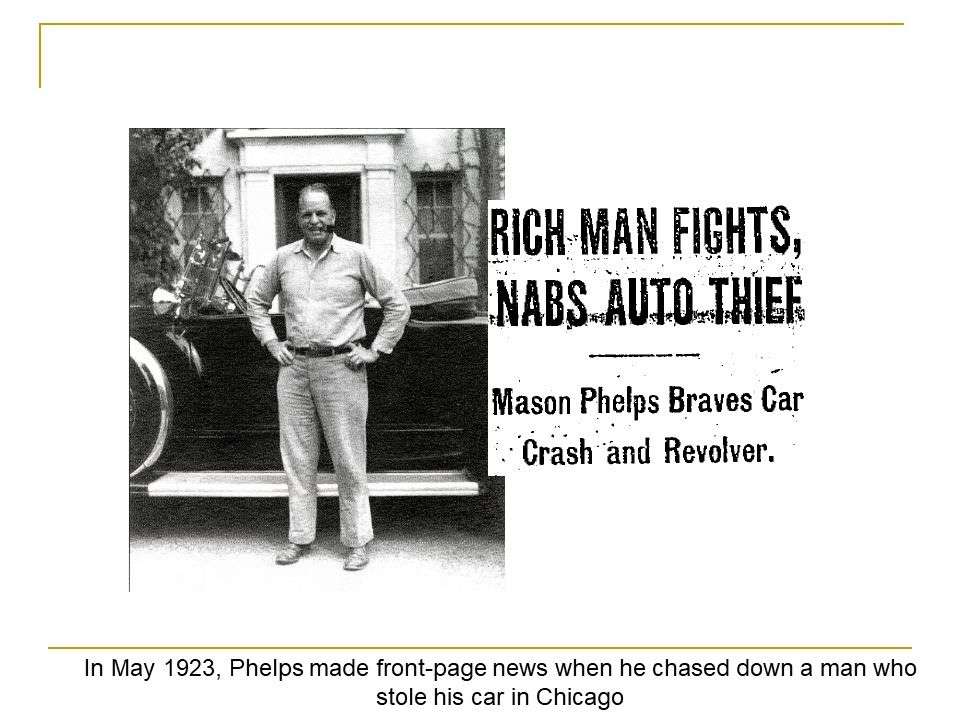

In 1923, Mason Phelps made the front page of the Chicago Tribune for a daring deed. One May evening, he was coming out of the Blackstone hotel on South Michigan boulevard when he spotted a thief driving away in his Marmo roadster car, which was parked right outside. He rapidly hailed a taxi and explained the circumstances to the driver, who agreed to try to overtake the thief. The two cars darted in and out of traffic down the boulevard at breakneck speed, until they caught up, pulled up alongside the thief, edged him to the curb, and the two cars crashed together. Mason Phelps leapt out of the taxi into his own car only to have the muzzle of a revolver pressed into his stomach. Phelps and the thief grappled for the gun, shortly joined by a South Park policeman who spotted the crash. The policeman also lunged at the thief, and between the policeman and Phelps, they were able to overpower and disarm him. The thief claimed he was simply going for a joyride in the park, but 45 rounds of ammunition were found on him and they suspected he was planning a holdup.

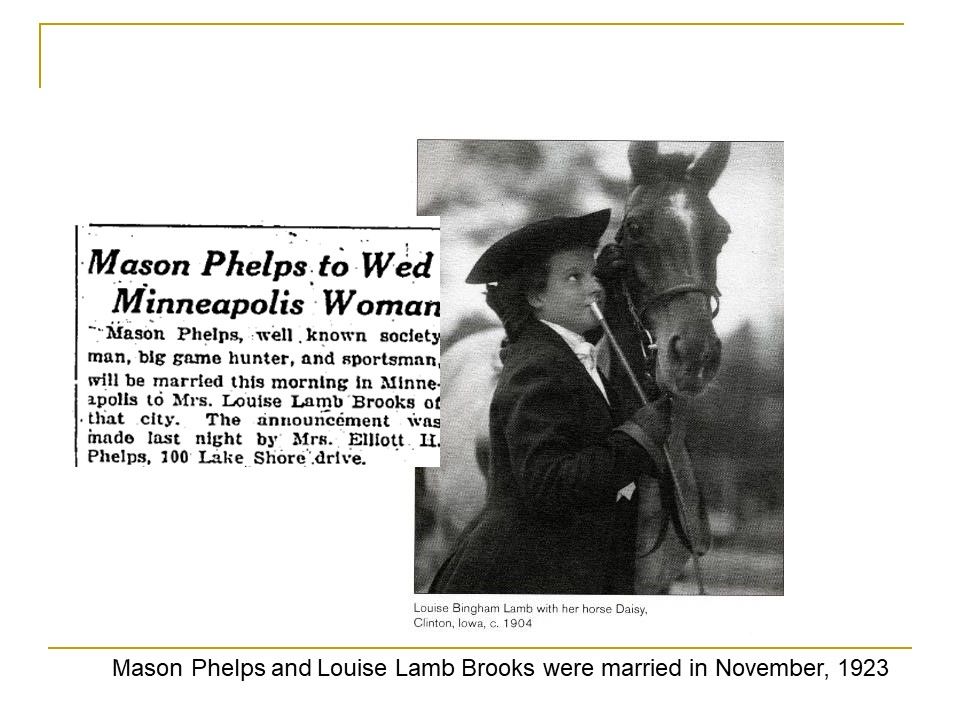

Around the time of all of this excitement, Mason Phelps was renewing his friendship with Louise Lamb Brooks, who he had known years before in Chicago and who he became reacquainted with at a golf tournament in Minneapolis, which is where she had grown up. They were married in November of 1923. It was a second marriage for Louise as well.

Their relationship began on the golf course and over the many years of their marriage the game of golf put it through various trials by fire. I refer here of course to the Shoreacres Benedict Cup, an alternate shot husband-wife tournament that has proven a test to many marriages. Theirs survived many years of Benedict Cups, but on one occasion it was a bit touch and go for awhile. On the 11th hole, Mason hit the drive right up to the plateau over the ravines. The next shot was an exceedingly tricky, difficult one. It was Louise’s turn, and like a good partner, she consulted with her husband, the Olympic champion golfer. “Mason, what do you suggest I do?” she asked. “My dear,” he said, “I suggest you whiff.” In response – and the only proper response to this, really – she walked off the course.

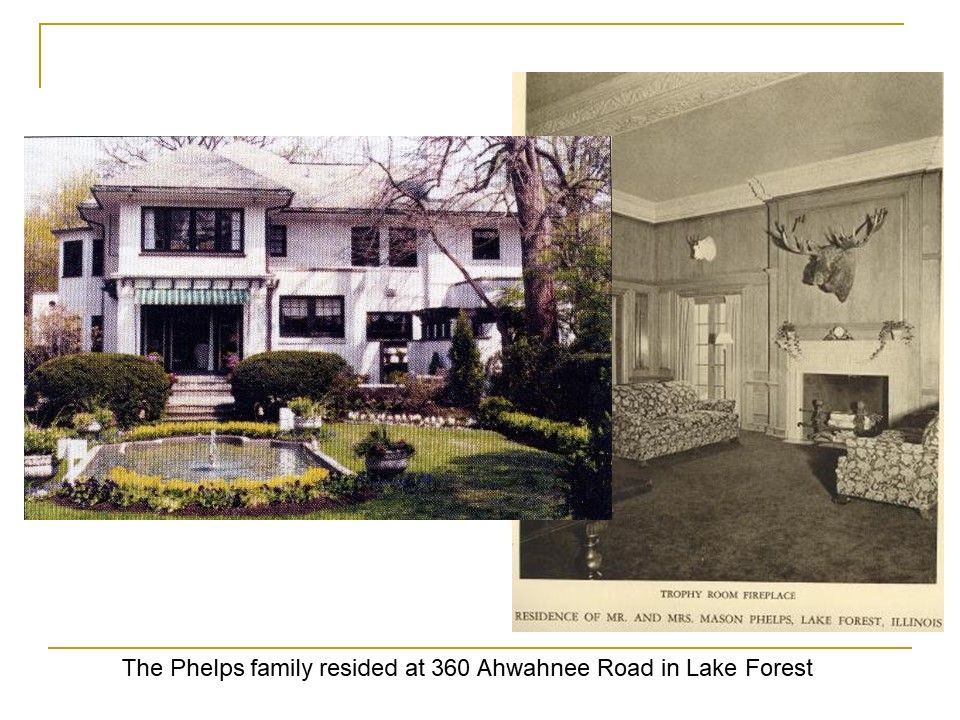

Mason

and Louise made their home in Lake Forest, in an Italian Renaissance

Revival house on Ahwahnee Road that had originally been built in 1912

for William Niblack by the architects Chatten and Hammond; Jens Jensen

designed the original landscape. In 1928, they added a large south wing,

designed by Stanley Anderson. The landscape architect Annette Hoyt

Flanders redid the terrace and garden in 1937.

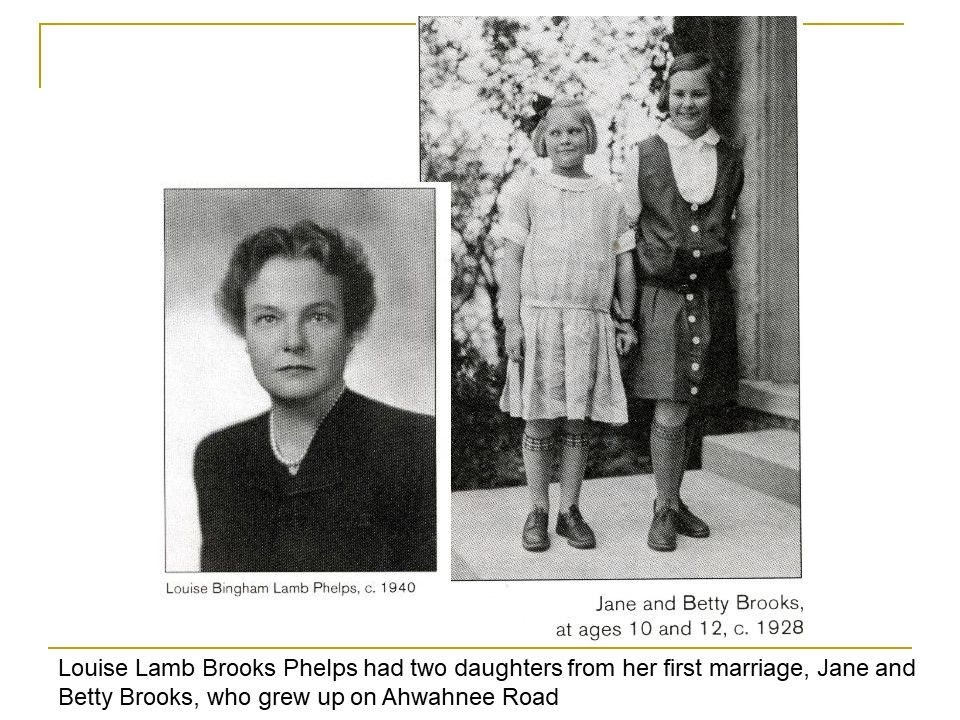

Living here with Mason and Louise were Louise’s two daughters from her first marriage, Jane and Betty Brooks, born in 1916 and 1918.

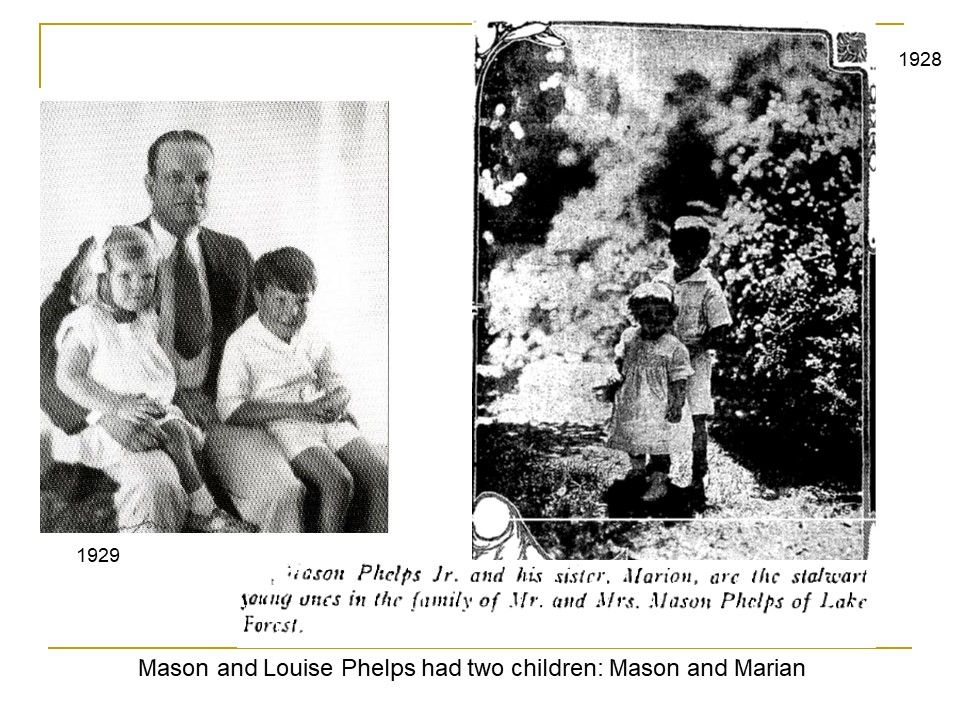

Shortly, Jane and Betty were joined by two younger siblings, Mason Phelps and Marion Phelps. Marian was named in honor of a friend of her father’s, the champion female golfer Marion Hollins, also a pioneering woman golf course developer. Marion Hollins spelled Marion with an “O,” M-A-R-I-O-N. Later in life, Marian Phelps changed the “O” to an “A,” to reflect the more common feminine spelling of the name.

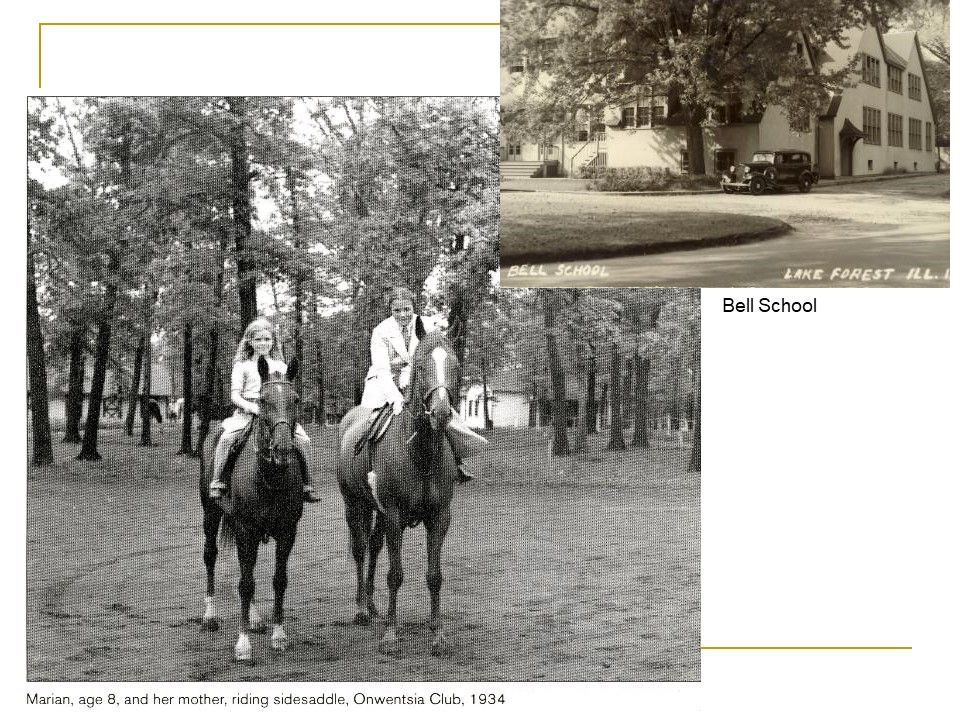

Mason and Marion were close in age and grew up playing together. They attended the Bell School, where Marian developed an early interest in art. She took private lessons from the Bell School’s art teacher, Mr. Nash, on Saturdays. Often the subject of her work were horses, most particularly her own retired polo pony, Nancy, who arrived one year at Christmas pulling a sleigh. Nancy was housed at a commercial stable on Bradley Road and often ridden at the Onwentsia Club with her mother, a talented horsewoman, riding sidesaddle, of course. When Marian was 9, she entered a show at Fort Sheridan for riders 18 and under…and won, largely, she claims, on the foundation of Nancy’s skill rather than her own.

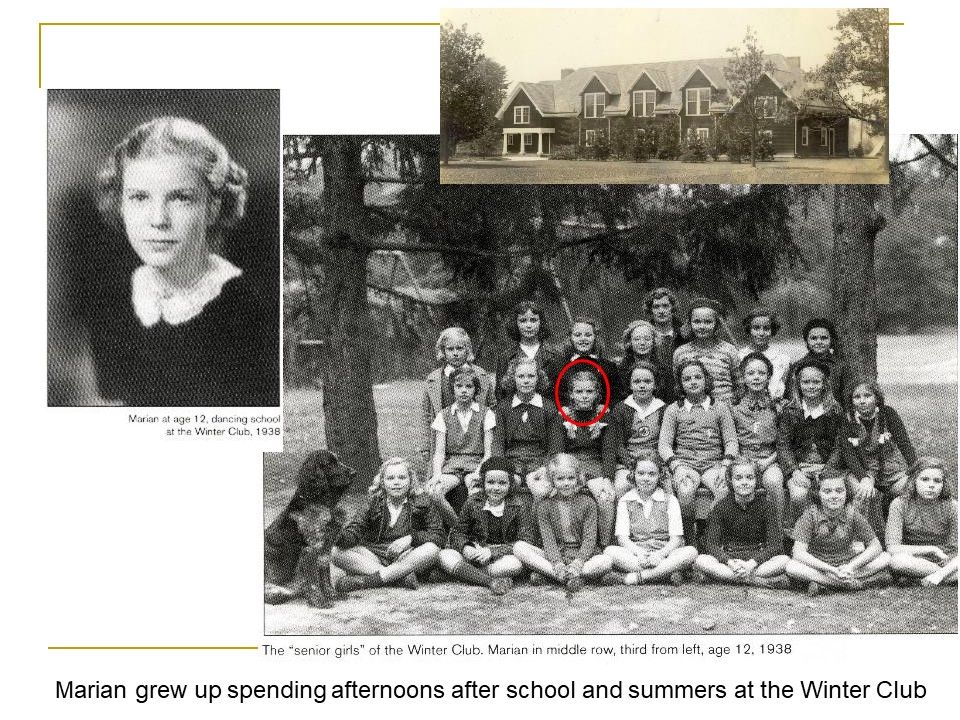

Often, summer days and afternoons after school were spent at the Winter Club. Typically Marian and Mason would ride their bicycles, but for a few years in the 1930s following the abduction of the Lindbergh baby, the Phelps’ (along with many other Lake Forest parents) became more cautious. Mason hired a private eye to chaperone the two children to and from school and the Winter Club, an endless embarrassment to Marian and Mason, who attempted to ditch their overseer whenever they were allowed to ride their bicycles.

Under the direction of Coach Sweeney at the Winter Club, Marian participated in all sorts of sports, including swimming and ice skating. Despite her genes and her namesake, she never took up golf as a child, not wanting to fall short of familial expectations – instead, since her father never learned to swim, she became an adept swimmer.

To a large extent the Phelps children kept on the straight and narrow, but there was one occasion when Mason and some of the other neighborhood boys got in trouble for shooting out some of the Lake Forest street lamps. They were apprehended by the police and taken to the jail at the police department. All of the other boys’ fathers came to retrieve their sons, but Mason stayed firm; Mason Jr remained there all night, surely learning his lesson, because he had to share a cell with a drunk who threw up.

Each summer, the Phelps family took a three-week trip, often traveling in Europe. In 1933, they traveled to Russia just after it opened again to foreign visitors. Mason had his camera confiscated when spotted changing film in Red Square. In 1936 they traveled to Berlin to see the Summer Olympics. Her father, having an Olympic gold medal, always felt a special connection to the Games. But this occasion was different. Marian remembers feeling uncomfortable in the tense, martial atmosphere.

After the Bell School, Mason attended Eaglebrook, Andover, and then Yale; he was a freshman in school when World War II broke out. At age 17, he secured his father’s permission to join the Marine Corps. Several years later, he was among the troops scheduled to invade Japan before the atomic bomb was dropped and the war ended.

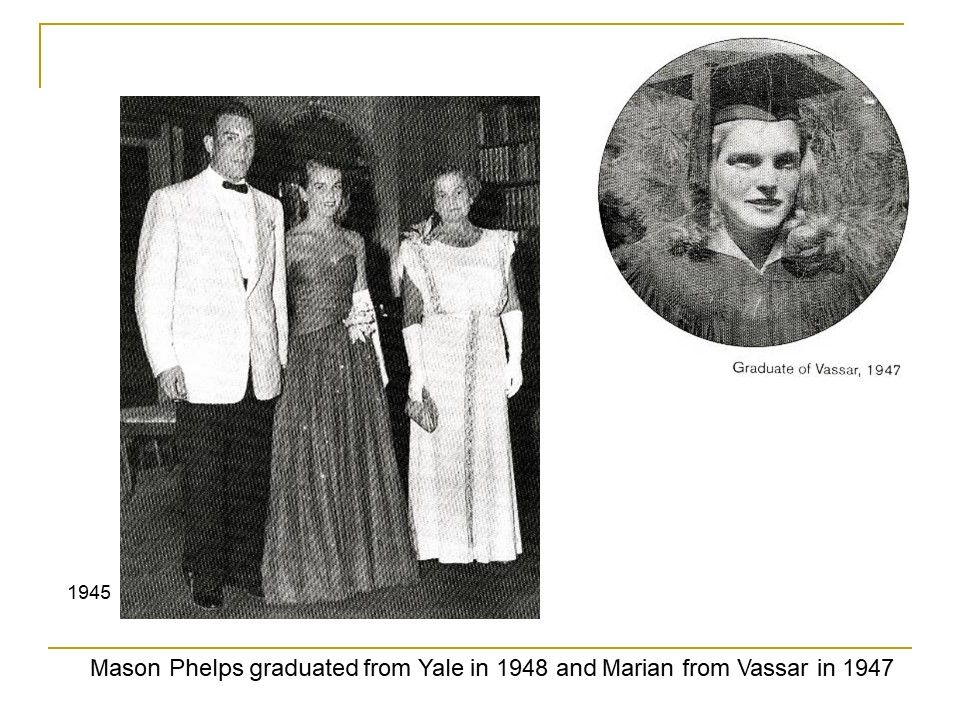

Marian attended Miss Hall’s in Massachusetts where, with her father’s threat of “finishing school” over her head, she began to concentrate on her studies. Soon she was accepted at Vassar College, where she studied art with Dr. Krautheimer, minoring in philosophy.

The fall of 1945 brought with it the end of the war, but it was a sad time for the Phelps family: Mason Phelps Sr died at only age 60 that September following a heart attack.

The postwar years brought a flurry of weddings in the Phelps family, as it did for so many others. Mason Jr. was married in 1947. After graduating from Yale, he entered the Pheoll Company in the boiler room, working his way up to management. With the rapid changes in production and technology occurring after the war, in 1950 Mason relocated to California to try to move the fastener business into the aerospace industry. He acquired a company, VSI, that worked out how to extrude titanium to produce screws to hold the Apollo together; Mason was later given a piece of the moon in recognition of this work. The family had come a long way – but not too far – from the early roots of the Mason family, who sold carriage bolts at their store in Wisconsin in the 1800s.

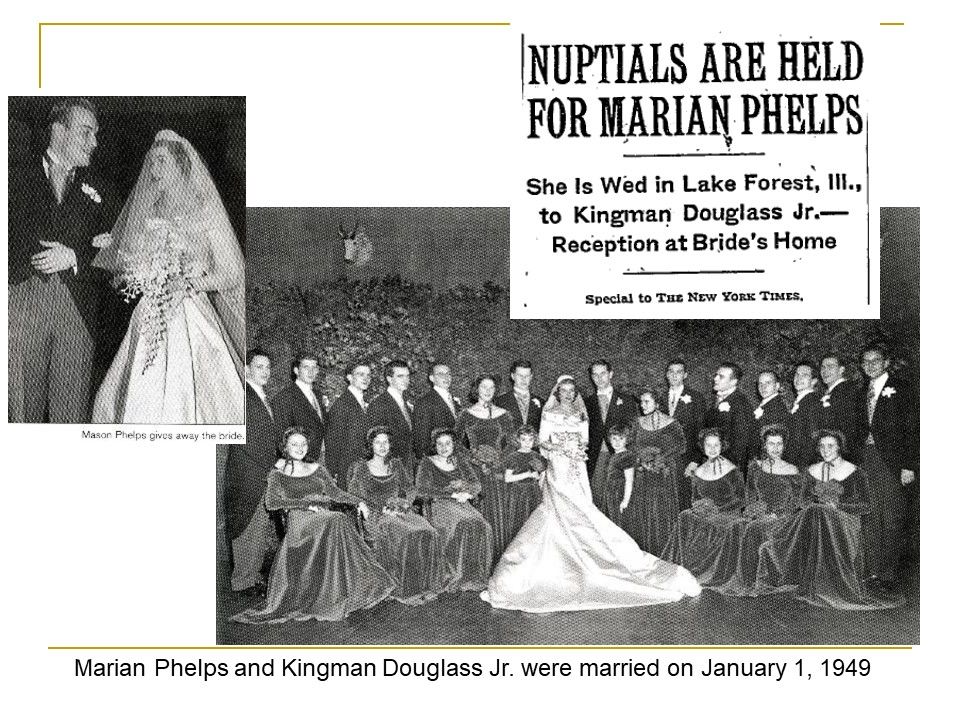

On New Year’s Day, 1949, Marian was married to Kingman Douglass, a Lake Forester who also attended Yale that she got to know through her brother. Mason Jr. gave the bride away at the wedding at First Presbyterian Church in Lake Forest.

Another family wedding took place in 1949: Marian’s mother, Louise, remarried to Alfred Cowles, who the children called Uncle Bob.

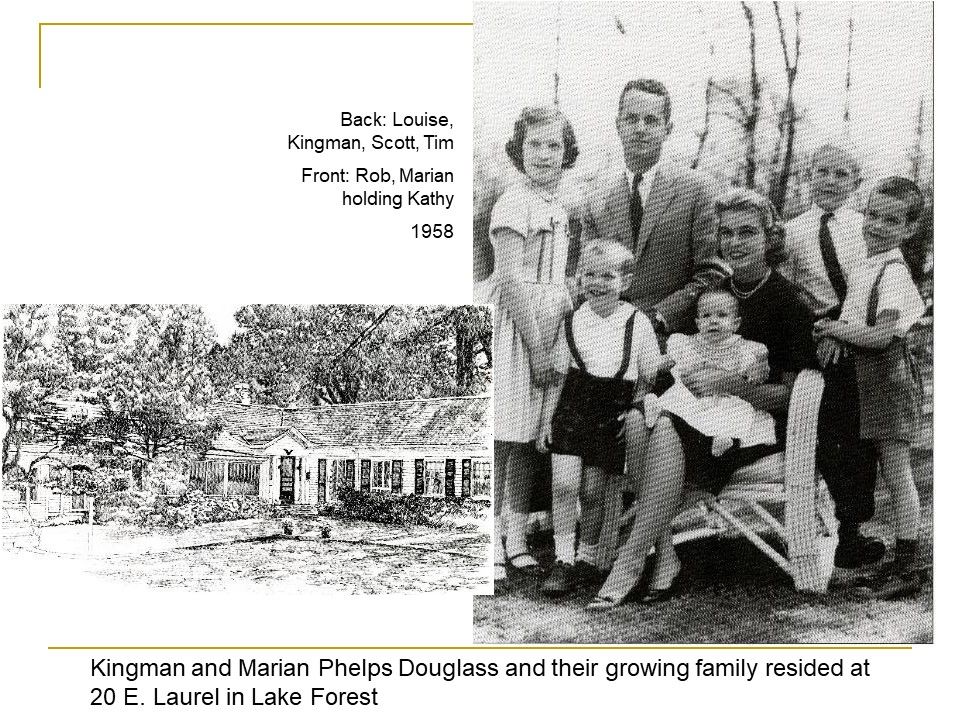

After they were married, Marian and Kingman moved around quite a bit for his job; by the late 1950s, though, they had settled in Lake Forest with their growing family. You can see the photo from 1958: Louise, Kingman, Scott and Tim in the back row, and Rob in front next to Marian holding baby Kathy. They bought a house at 20 E. Laurel – after moving in and heading down into the basement, Marian suddenly realized that she had attended preschool in that very house, in that very basement, as a young girl.

The children grew up attending the Bell School and playing sports at the Winter Club before going off to prep school. Like the previous generation, they typically rode their bicycles, but in the colder months Marian would shuttle around the kids’ carpools in a 1926 woody Ford station wagon – actually a relic of a previous generation. When the older children got their licenses, they drove the wagon, with its maximum speed of 30 mph, in lieu of the sports car that some of their classmates received.

Marian continued to paint and pursue her passion for art. In the 1950s she was one of about thirty founding members of the Deer Path Art League, which held its first art fair in Market Square in 1955 with 15 entries and $50 in the bank. Quickly it grew, offering painting classes and opening a gallery in Market Square.

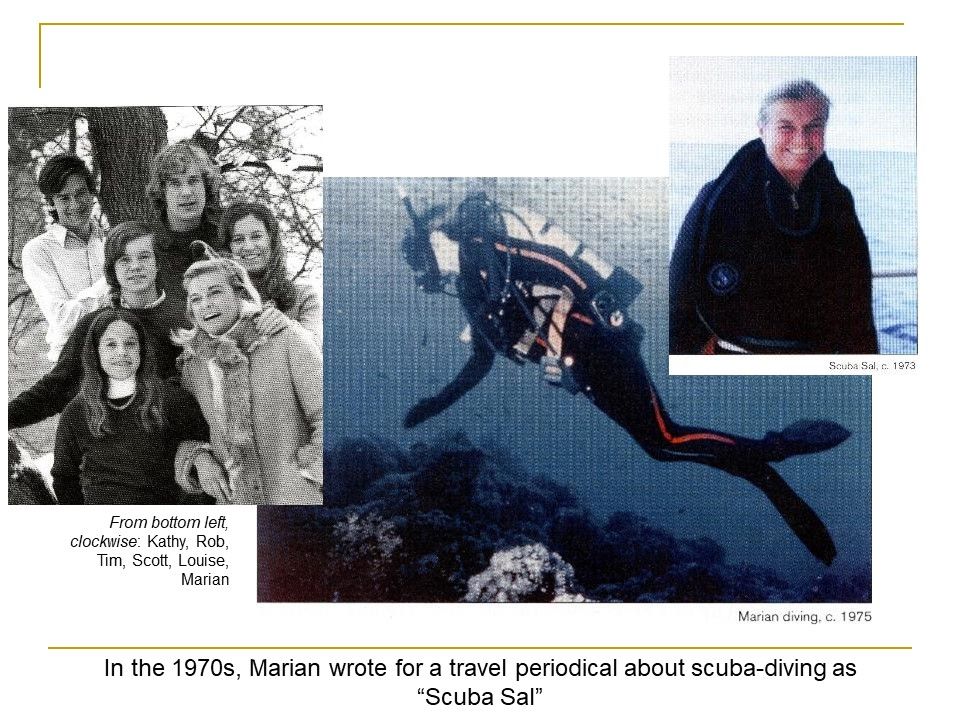

In 1971, Marian and Kingman divorced. Shortly thereafter, a chance encounter on, of all things, the golf course brought an unexpected opportunity. Marian began to write for a travel periodical called Passport. As I mentioned, she was a strong swimmer since childhood, and she became Passport’s “underwater reporter” for a new sport called scuba-diving. She got certified, and since her children were all in college or prep school, was able to begin to travel around the world to review different dives. She signed her articles “Scuba Sal.”

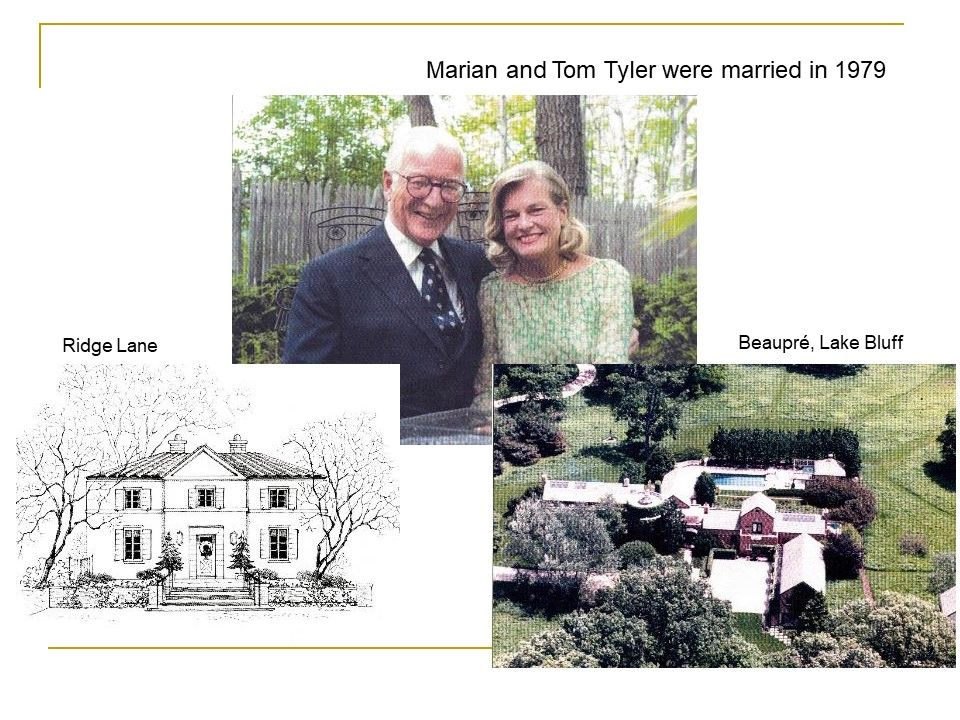

Marian’s eldest daughter Louise was married in 1978, and at the reception, she hurled the bouquet at her mother. Marian was a little taken aback, but her date, Tom Tyler, thought it was fine, and the next year, they were married. Tom was a partner at the law firm of Winston & Strawn – the same firm started by Silas Strawn, her father’s very first investor.

At first they lived in Lake Forest on Ridge Lane. In 1985, they bought one of the lots on the William McCormick Blair Crab Tree Farm property, and in 1987 they had architect Ed Noonan build a house they called Beaupre, or “beautiful meadow.”

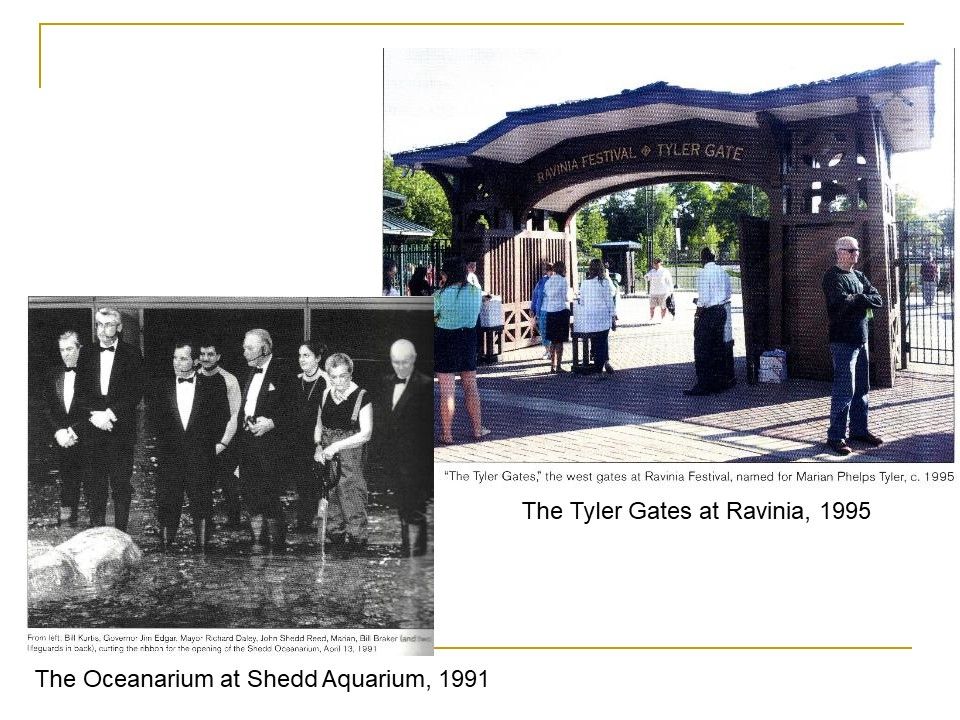

Besides the Deer Path Art League, the family supported many other Lake Forest and Chicago cultural and educational institutions. Marian served on the boards of Lake Forest College, Vassar College, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and others. Her experience scuba-diving led to her involvement with the Shedd Aquarium, helping provide diversity and fund-raising prowess to a board that had been populated by retired men with recreational interest in fishing. Her work helped get the new Oceanarium constructed in 1991. She also joined the board of the Ravinia Festival, and the Tyler gates, the west gates at Ravinia, are named for Marian Phelps Tyler.

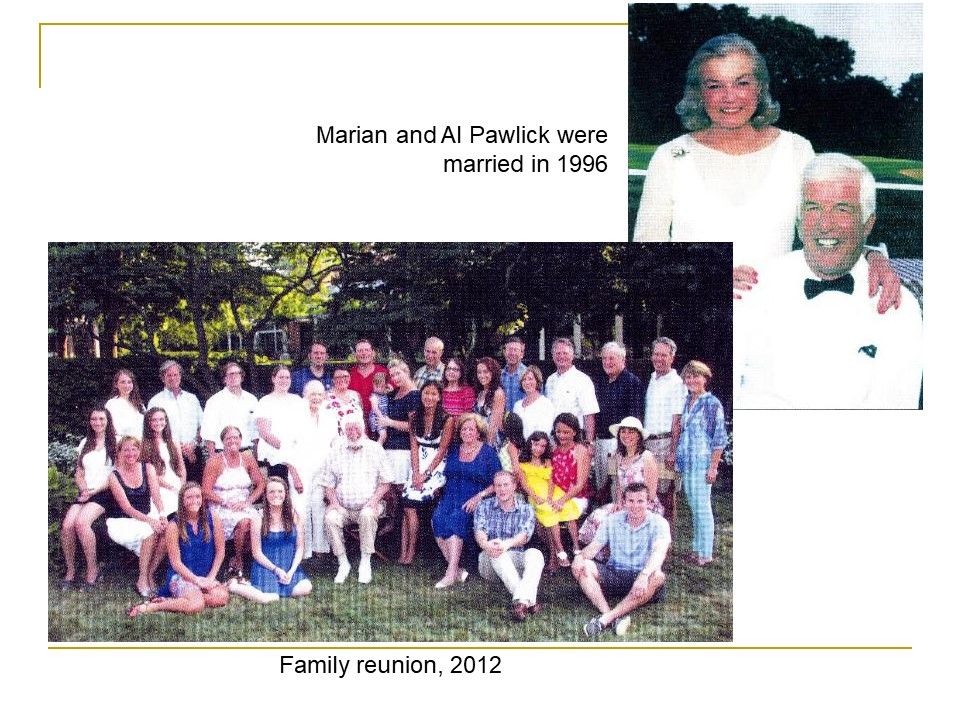

Back in the 1940s, during the summer before she went to Vassar, Marian visited Pebble Beach with a school friend. The two decided it would be fun to have their palms read and visited a fortune teller, a mildly frightening woman who stared at Marian’s hand and told her, “You will be married three times.” Tom Tyler, who was several years older than Marian, passed away in 1994. Al Pawlick was a widower as well: before she died, his wife Peggy had given him a list of three women she thought he’d be compatible with, knowing he would not enjoy being alone. After successfully navigating a golf foursome together, they began seeing each other, and in 1996 they were married, fulfilling a 50-year-old prophecy. You can see the many branches of their wonderful family here, gathered in Lake Bluff.